8 Statistical variables

8.1 Estimandum, estimands and statistical variables

Statistical variables are a fundamental aspect of quantitative data analysis. There isn’t an agreed upon definition of a statistical variable, but generally speaking, anything that you have measured or counted is a statistical variable. For example, let’s say you want to measure language proficiency in L2 learners: “language proficiency” is your estimandum, i.e. the concept or entity you wish to measure; you decide to measure language proficiency using the score of a proficiency test, this is the estimand, i.e. the specific measurement of the estimandum “language proficiency”. When the estimand can take on different values, the estimand is a statistical variable: every participant will have a different proficiency score.

Language research involves a large variety of statistical variables. Here just a few examples:

- Token number of telic verbs and atelic verbs in a corpus of written Sanskrit.

- Voice Onset Time of stops in Mapudungun.

- Friendliness ratings of synthetic speech.

- Accuracy of responses in a lexical decision task.

- Digit memory span.

- Phrasal headedness (head-initial vs head-final).

Try and think of more!

So a statistical variable is a measured characteristic. More specifically, a statistical variable is also a mathematical construct: the outcome of the specific mathematical process that generates the values that can be observed and measured. In the case of language proficiency, the statistical variable “proficiency test score” is generated by a process that includes a lot of factors (which can themselves be construed as statistical variables), like actual proficiency, stress levels when taking the test, baseline memory capacity, years of learning and so on. The generative process, i.e. the process that generates the values of a statistical variable, is ultimately what the researcher is interested in.

When you observe or measure something, i.e. when you collect a sample, you are taking note of the values of the statistical variable generated by the generative process. We call them statistical variables because each time you sample the variable, you get different values. In other words, the generative process allows for variation in the output values. The opposite of a variable is a called a statistical constant. Generative processes can contain both variables and constants. Statistical variables and constants are two types of estimands. In practice, you don’t have to worry about whether something is a variable or a constant and in most research contexts you will be working with statistical variables.

8.2 Types of variables

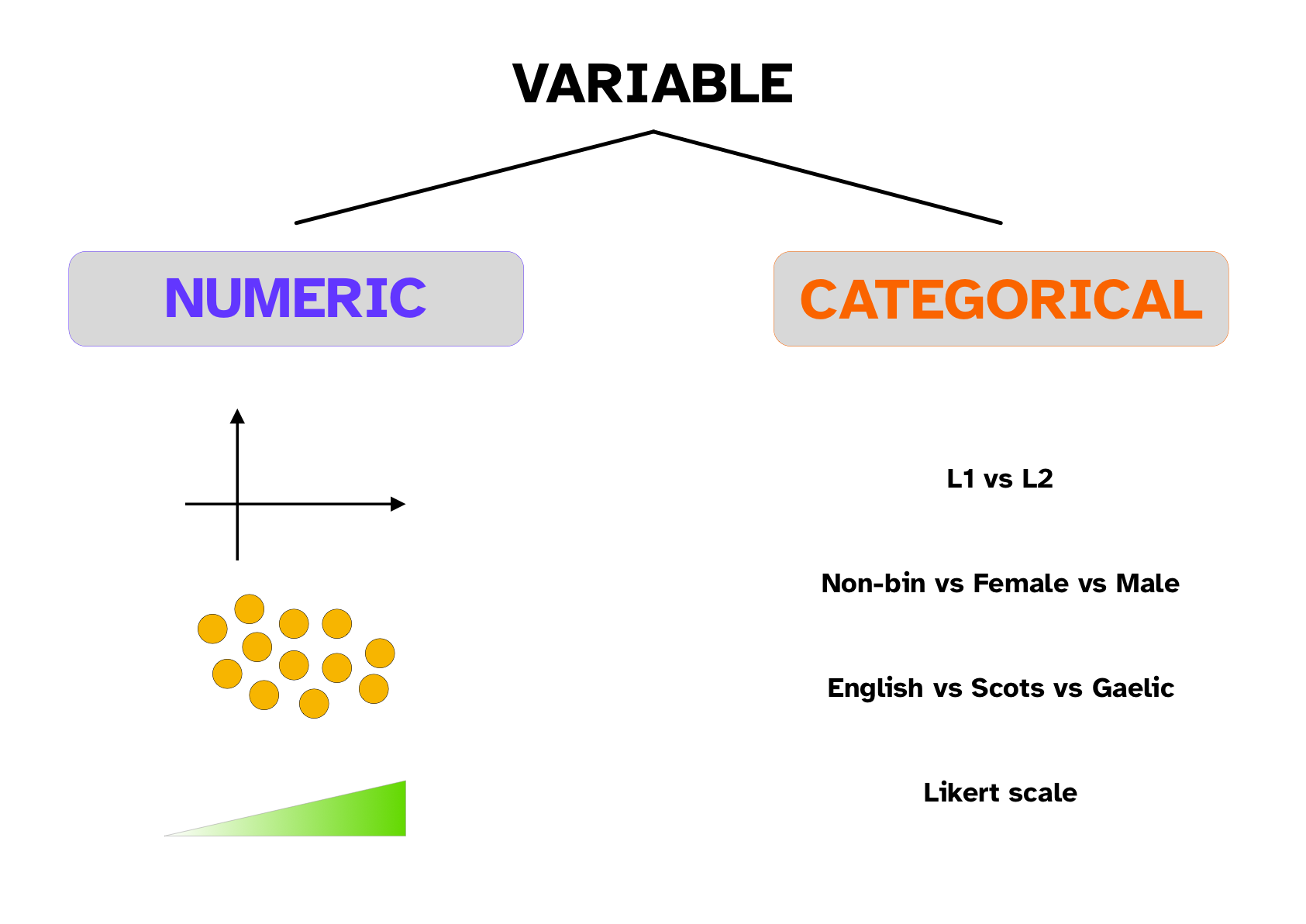

You will find that some statistics textbooks overcomplicate things when it come to types of statistical variables. From an applied statistics perspective, you only need to be able to identify numeric vs categorical variables and continuous vs discrete variables.

8.2.1 Numeric vs categorical variables

The distinction is quite self-explanatory:

Numeric variables are variables that are numbers.

Categorical variables are variables that correspond to categories, groups or levels on a scale.

Learning how to recognise variables is a fundamental skill in quantitative data analysis, since the type of variables determines the type of analyses you can carry out.

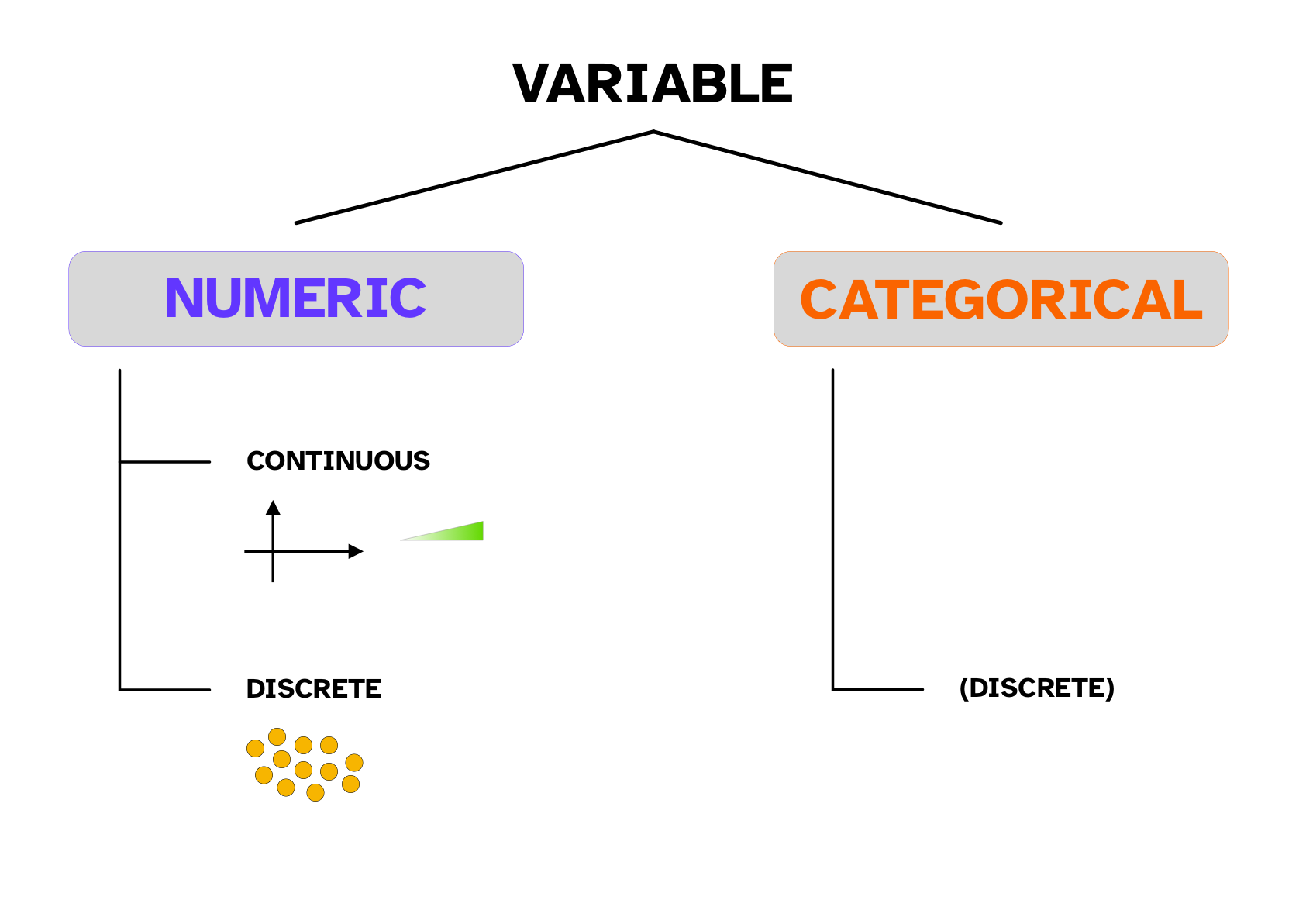

8.2.2 Continuous vs discrete variables

Orthogonal to the numeric/categorical distinction, there is the continuous vs discrete distinction. This one can be at times less straightforward.

A continuous variable is a variable that can take on any value between any two numbers. For example, speech segment duration can be 0.2 s, 0.25 s, 0.2534 s and so on. Segment duration is continuous.

A discrete variable is a variable that can only take on a set of values, and no value in between. For example, number of gestures is discrete because you can measure 1, 2, 3, 10 gestures but not 3 gestures and three quarters.

Numeric variables can be either continuous or discrete, while categorical variables can only be discrete. There are also sub-types of numeric continuous, numeric discrete and categorical (discrete) variables. The following call-out introduces these sub-types, with examples.

8.3 Operationalisation

It should be clear now that the estimand is not quite the same thing as the estimandum. The estimand is the researcher’s way to capture the estimandum so that it can be analysed. The relationship between the estimandum and the estimand variable is called operationalisation: an estimandum is operationalised into an estimand. The action of operationalisation consists in choosing how to measure something: as a numeric or as a categorical variable. In some cases, the choice is obvious, but in most cases something could be operationalised either way and different considerations have to be taken into account when choosing, like the particular framework adopted and the study design.

Let’s think about “age” for a moment: age can be operationalised as years or months (numeric discrete) or as age bins, like young vs old (categorical). Different studies might require one or the other operationalisation of the estimandum “age”. Another example is “acceptability” in morphosyntactic studies: acceptability can be operationalised as a binary categorical variable (grammatical vs agrammatical, and we normally talk of “grammaticality”), as a categorical scale (acceptable, somewhat acceptable, somewhat not acceptable, unacceptable), or a numeric continuous scale (0 to 100). It is important, when planning a study, to carefully think about estimanda (the plural of estimandum) and estimands and how their relationship could be less clear than one might think.