67 - 13

2 * 4

268 / 434 R basics

4.1 Why R?

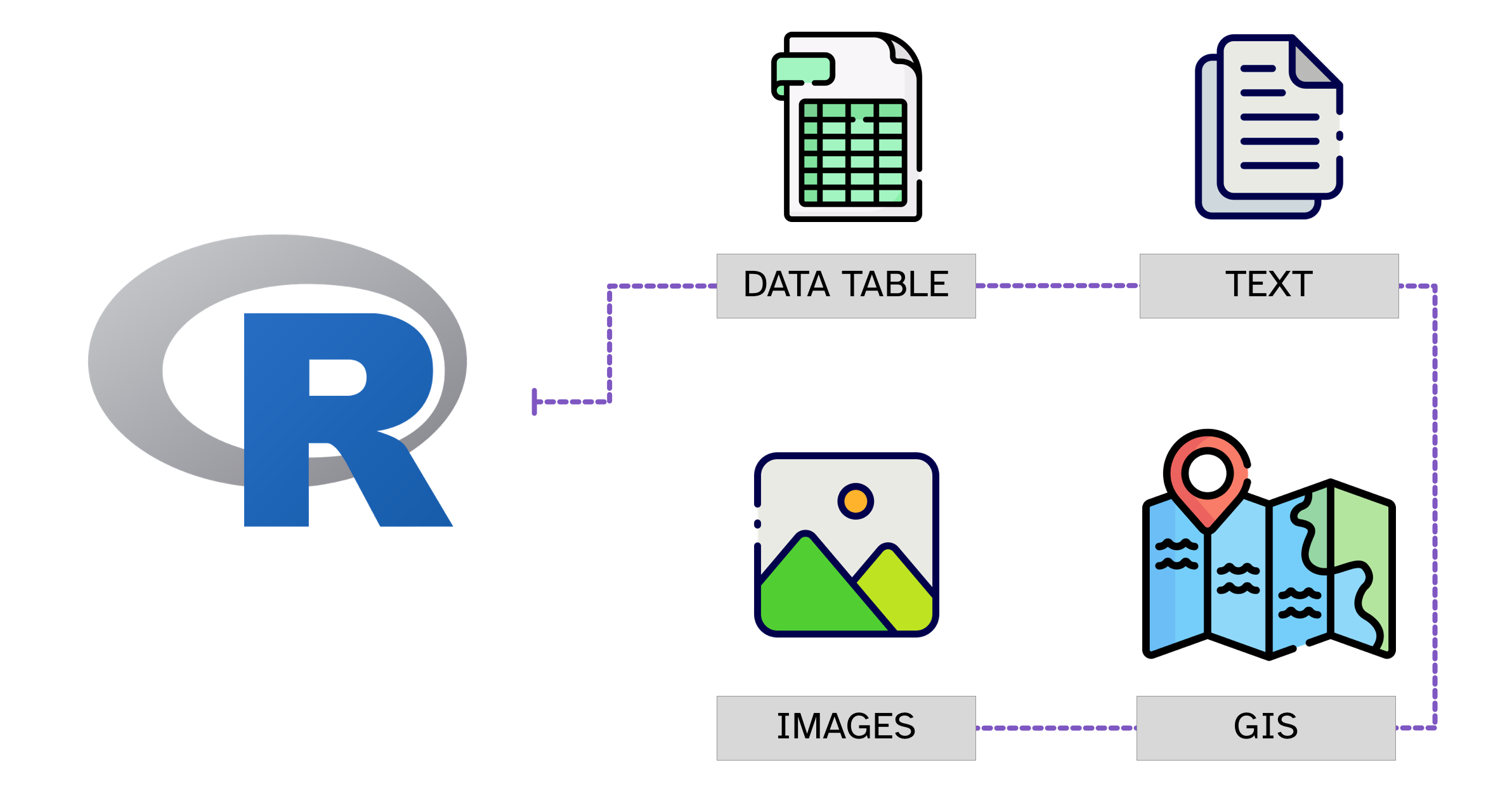

R can be used to analyse all sorts of data, from tabular data (also known as “spreadsheets”), textual data, map (GIS, Geographic Information System) data and even images.

This course will focus on the analysis of tabular data, since all of the techniques relevant to this type of data also apply to the other types.

The R community is a very inclusive community and it’s easy to find help. There are several groups that promote R in minority/minoritised groups, like R-Ladies, Africa R, and Rainbow R just to mention a few.

Moreover, R is open source and free for anyone to use!

4.2 R vs RStudio

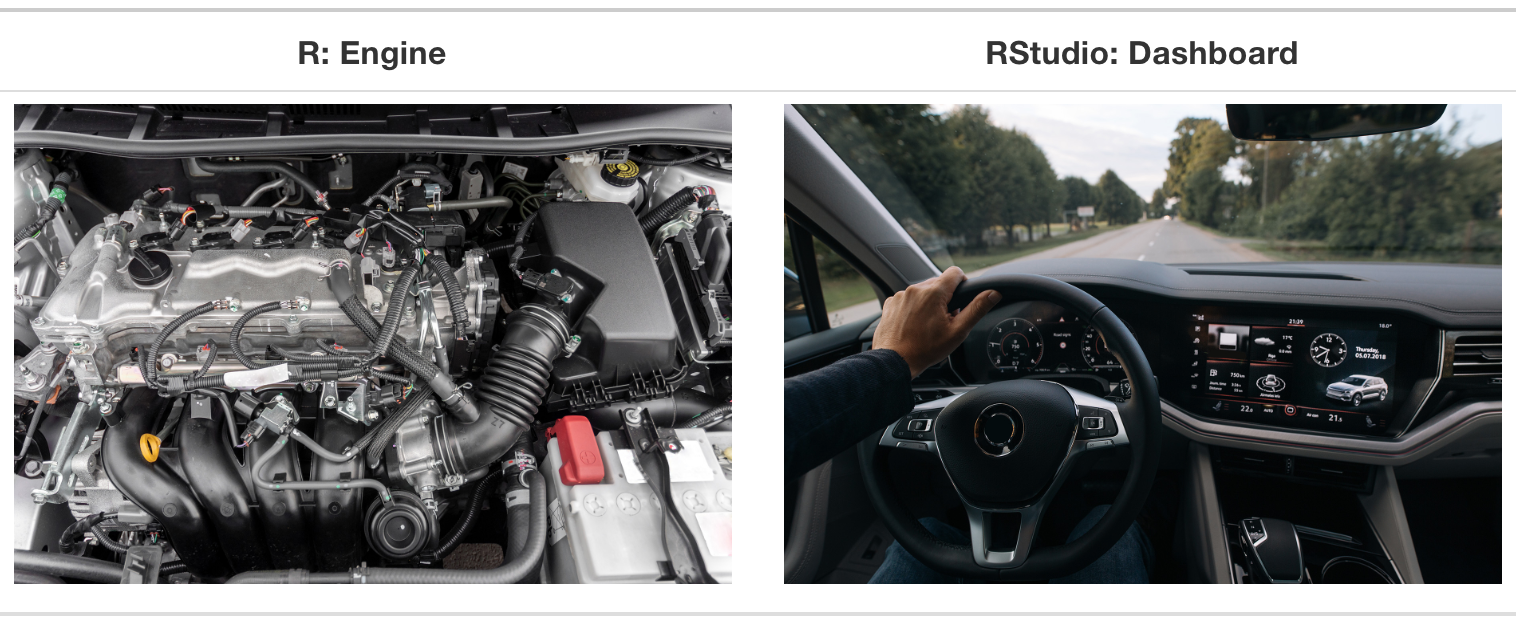

Beginners usually have trouble understanding the difference between R and RStudio. Let’s use a car analogy. What makes the car go is the engine and you can control the engine through the dashboard. You can think of R as an engine and RStudio as the dashboard.

The next section will give you a tour of RStudio.

4.3 RStudio

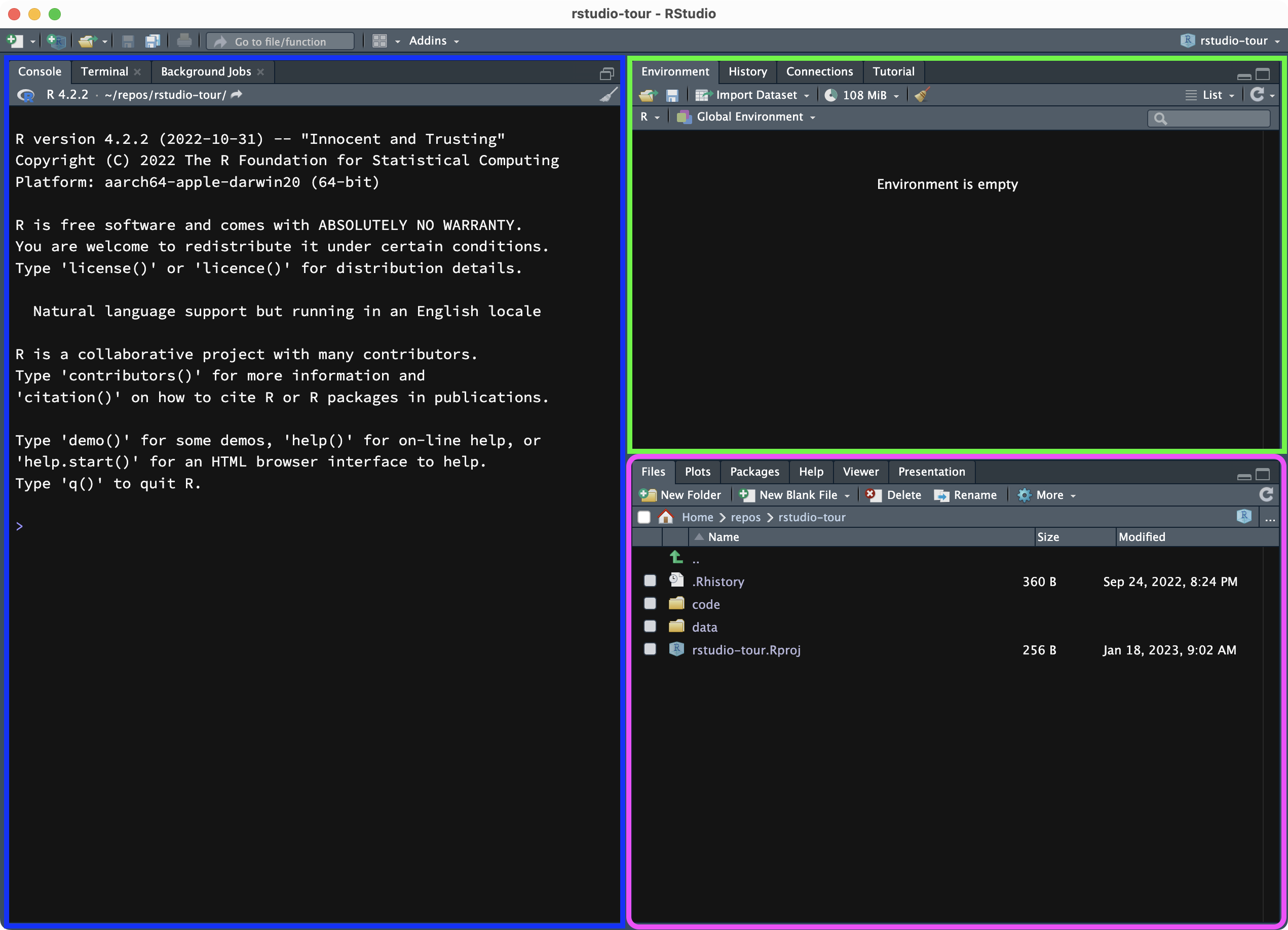

Open RStudio on your computer and familiarise yourself with the different parts. When you open RStudio, you can see the window is divided into 3 panels:

Blue (left): the Console.

Green (top right): the Environment tab.

Purple (bottom right): the Files tab.

The Console is where R commands can be executed. Think of this as the interface to R. Now, try to run (execute) some R code in the console:

The Environment tab lists the objects created with R, while in the Files tab you can navigate folders on your computer to get to files and open them in the file Editor.

4.3.1 RStudio and Quarto projects

RStudio is an IDE (see above) which allows you to work efficiently with R, all in one place. Note that files and data live in folders on your computer, outside of RStudio: do not think of RStudio as an app that you can save files in. All the files that you see in the Files tab are files on your computer and you can access them from the Finder or File Explorer as you would with any other file.

In principle, you can open RStudio and then navigate to any folder or file on your computer. However, there is a more efficient way of working with RStudio: RStudio and Quarto Projects.

You can create as many Quarto Projects as you wish, and I recommend to create one per project (your dissertation, a research project, a course, etc…). We will create a Quarto Project for this course (meaning, you will create a folder for the course which will be the Quarto Project). You will have to use this project/folder throughout the semester.

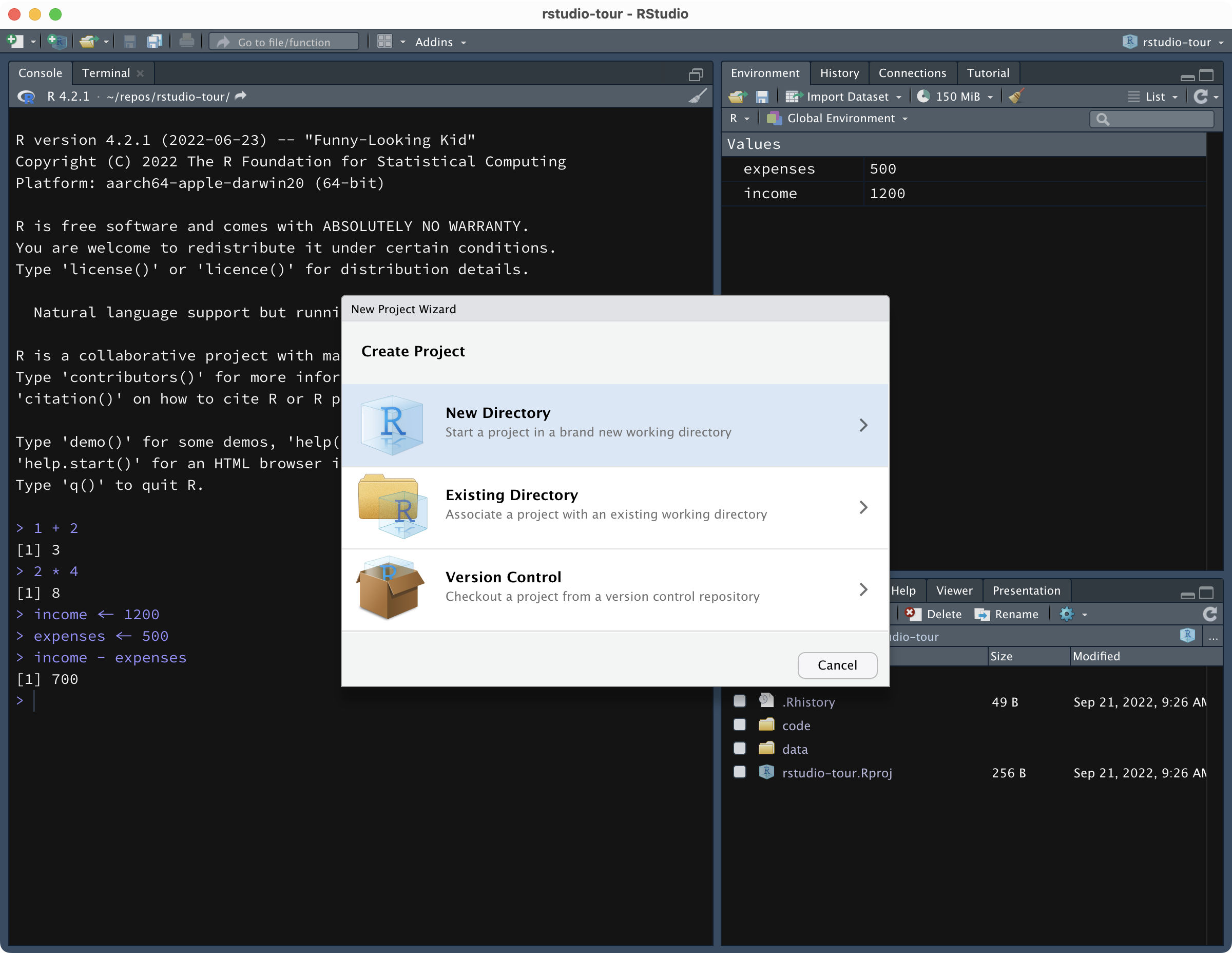

To create a new Quarto Project, click on the button that looks like a transparent light blue box with a plus, in the top-left corner of RStudio. A window like the one below will pop up.

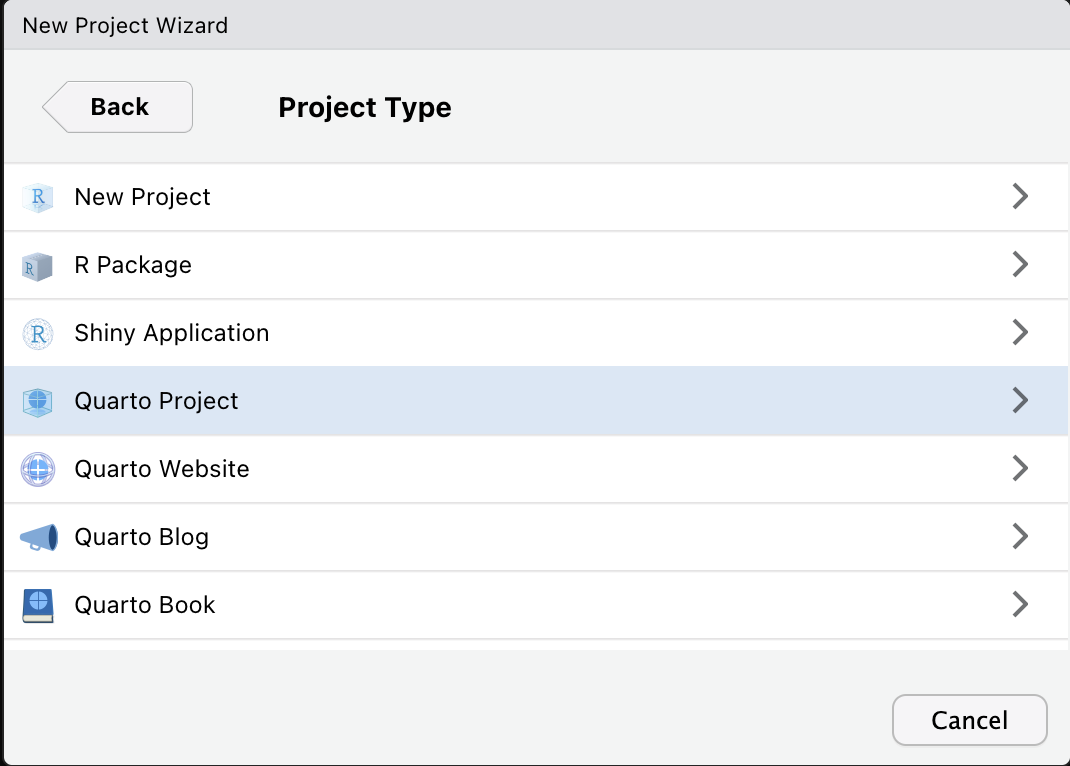

Click on New Directory then Quarto Project.

Now, this will create a new folder (aka directory) on your computer and will make that a Quarto Project (meaning, it will add a file with the .Rproj extension and a file called _quarto.yml to the folder; the name of the .Rproj file will be the name of the project/folder).

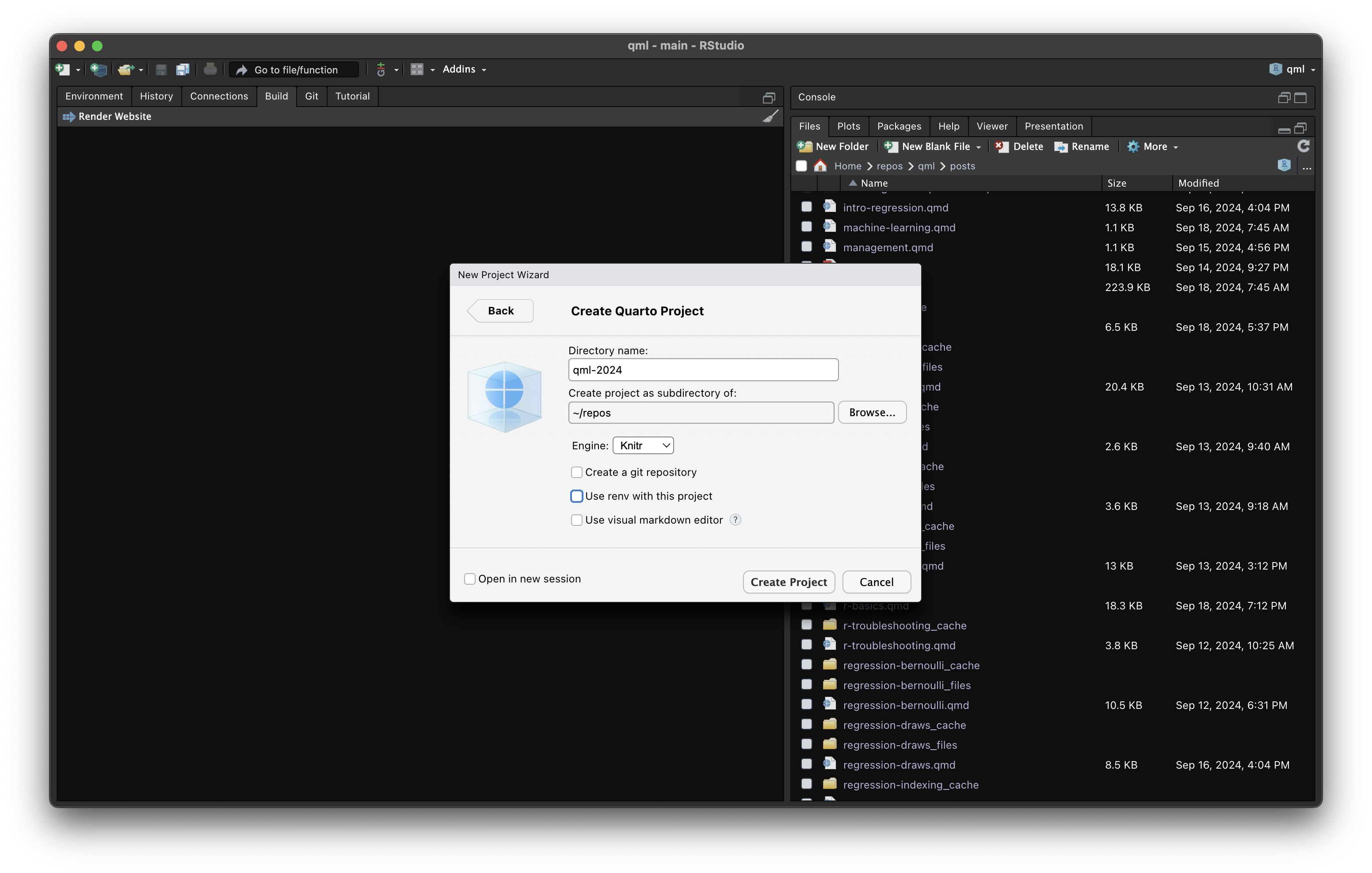

Give a name to your new project, something like the name of the course and year (e.g. qml-2025).

Then you need to specify where to create this new folder/Project. Click on Browse… and navigate to the folder you want to create the new folder/Project in. This could be your Documents folder, or the Desktop (we had issues with OneDrive in the past, so we recommend you save the project outside of OneDrive).

When done, click on Create Project. RStudio will automatically open your new project.

There are several ways of opening a Quarto Project:

You can go to the Quarto Project folder in Finder or File Explorer and double click on the

.Rprojfile.You can click on

File > Open Projectin the RStudio menu.You can click on the project name in the top-right corner of RStudio, which will bring up a list of projects. Click on the desired project to open it.

4.3.2 A few important settings

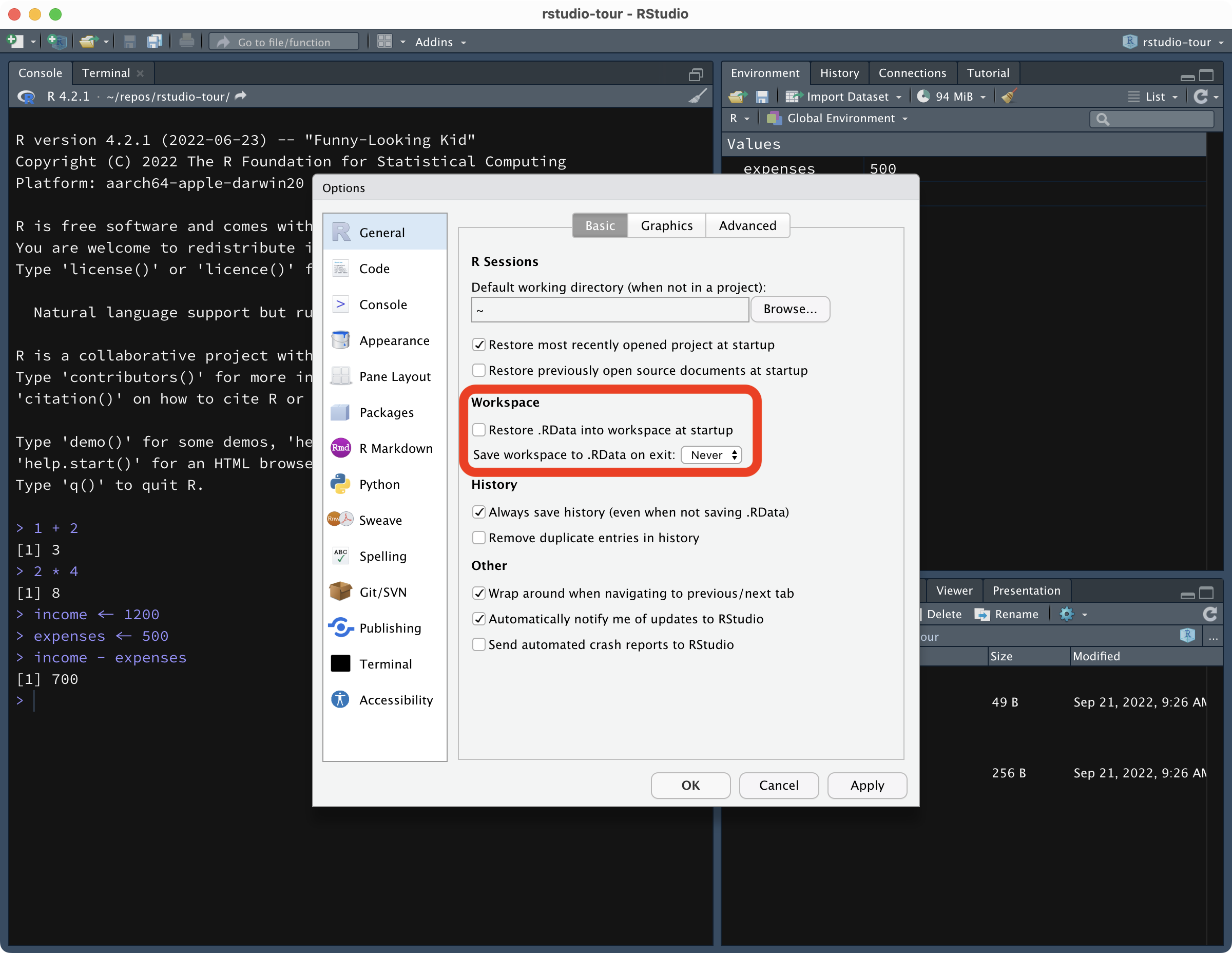

Before moving on, there are a few important settings that you need to change.

Open the RStudio preferences (

Tools > Global options...).Un-tick

Restore .RData into workspace at startup.- This mean that every time you start RStudio you are working with a clean Environment. Not restoring the workspace ensures that the code you write is fully reproducible. When this setting is enabled, your environment is saved in a hidden file called

.Rdataand loaded every time you start RStudio. This very frequently leads to errors where the wrong variables/data is read or used by the code without you noticing, so always make sure the setting is disabled.

- This mean that every time you start RStudio you are working with a clean Environment. Not restoring the workspace ensures that the code you write is fully reproducible. When this setting is enabled, your environment is saved in a hidden file called

Select

NeverinSave workspace to .RData on exit.- Since we are not restoring the workspace at startup, we don’t need to save it. Remember that as long as you save the code, you will not lose any of your work! You will learn how to save code from next week.

Click

OKto confirm the changes.

4.4 R basics

In this part of the tutorial you will learn the very basics of R. If you have prior experience with programming, you should find all this familiar. If not, not to worry! Make sure you understand the concepts highlighted in the green boxes and practise the related skills.

In the following sections, you should just run code directly in the R Console in RStudio, i.e. you will type code in the Console and press ENTER to run it.

In later chapters, you will learn how to save your code in a script file or in Quarto documents, so that you can keep track of which code you have run and make your work reproducible.

4.4.1 R as a calculator

Write this code 1 + 2 in the Console, then press ENTER/RETURN to run the code. Fantastic! You should see that the answer of the addition has been printed in the Console, like this:

[1] 3(Never mind the [1] for now).

Now, try some more operations (write each of the following in the Console and press ENTER). Feel free to add your own operations to the mix!

You can also chain multiple operations.

6 + 4 - 1 + 2

4 * 2 + 3 * 24.4.2 Variables

Forget-me-not.

Most times, we want to store a certain value so that we can use it again later.

We can achieve this by creating variables.

You can create a variable by using the assignment operator <-.

Let’s assign the value 156 to the variable my_num.

my_num <- 156Now, check the list of variables in the Environment tab of the top-right panel of RStudio. You should see the my_num variable and its value there.

Now, you can just call the variable back when you need it! Write the following in the Console and press ENTER.

my_num[1] 156A variable like my_num is also called a numeric vector: i.e. a vector that contains a number (hence numeric).

A vector is a type of variable and a numeric vector is a type of vector. However, it’s fine in most cases to use the word variable to mean vector (just note that a variable can also be something else than a vector; you will learn about other R objects in later chapters).

Let’s now try some operations using variables.

income <- 1200

expenses <- 500

income - expenses[1] 700See? You can use operations with variables too! And you can also go all the way with variables.

savings <- income - expensesAnd check the value…

savings[1] 700Vectors can hold more than one item or value. Just use the combine c() function to create a vector containing multiple values. The following are all numeric vectors.

one_i <- 6

# Vector with 2 values

two_i <- c(6, 8)

# Vector with 3 values

three_i <- c(6, 8, 42)Check the list of variables in the Environment tab. You will see now that before the values of two_i and three_i you get the vector type num for numeric. (If the vector has only one value, you don’t see the type in the Enviroment list but it is still of a specific type.)

Note that the following are the same:

one_i <- 6

one_i[1] 6one_ii <- c(6)

one_ii[1] 6Another important aspect of variables is that they are… variable! Meaning that once you assign a value to one variable, you can overwrite the value by assigning a new one to the same variable.

my_num <- 88

my_num <- 63

my_num[1] 634.4.3 Functions

R cannot function without… functions.

A function in R has the form function() where:

functionis the name of the function, likesum.()are round parentheses, inside of which you write arguments, separated by commas.

Let’s see an example:

sum(3, 5)[1] 8The sum() function sums the number listed as arguments. Above, the arguments are 3 and 5.

And of course arguments can be vectors!

my_nums <- c(3, 5, 7)

sum(my_nums)[1] 15mean(my_nums)[1] 54.4.4 String and logical vectors

Not just numbers.

We have seen that variables can hold numeric vectors. But vectors are not restricted to being numeric. They can also store strings. A string is basically a set of characters (a word, a sentence, a full text). In R, strings have to be quoted using double quotes " ".

Change the following strings to your name and surname. Remember to use the double quotes.

name <- "Stefano"

surname <- "Coretta"

name[1] "Stefano"surname[1] "Coretta"Strings can be used as arguments in functions, like numbers can.

cat("My name is", name, surname)My name is Stefano CorettaRemember that you can reuse the same variable name to override the variable value.

name <- "Raj"

cat("My name is", name, surname)My name is Raj CorettaYou can combine multiple strings into a character vector, using the combine function c() (the function works with any type of vectors, not only characters!).

fruit <- c("apple", "oranges", "bananas")

fruit[1] "apple" "oranges" "bananas"Check the Environment tab. Character vectors have chr before the list of values.

Another type of vector is one that contains either TRUE or FALSE. Vectors of this type are called logical vectors and they are listed as logi in the Environment tab.

groceries <- c("apple", "flour", "margarine", "sugar")

in_pantry <- c(TRUE, TRUE, FALSE, TRUE)

data.frame(groceries, in_pantry)TRUE and FALSE values must be written in all capitals and without double quotes (they are not strings!).

(We will talk about data frames, another type of object in R, in the following chapters.)

4.5 Summary

You made it! You completed this chapter.

Here’s a summary of what you learned.