2 Research context

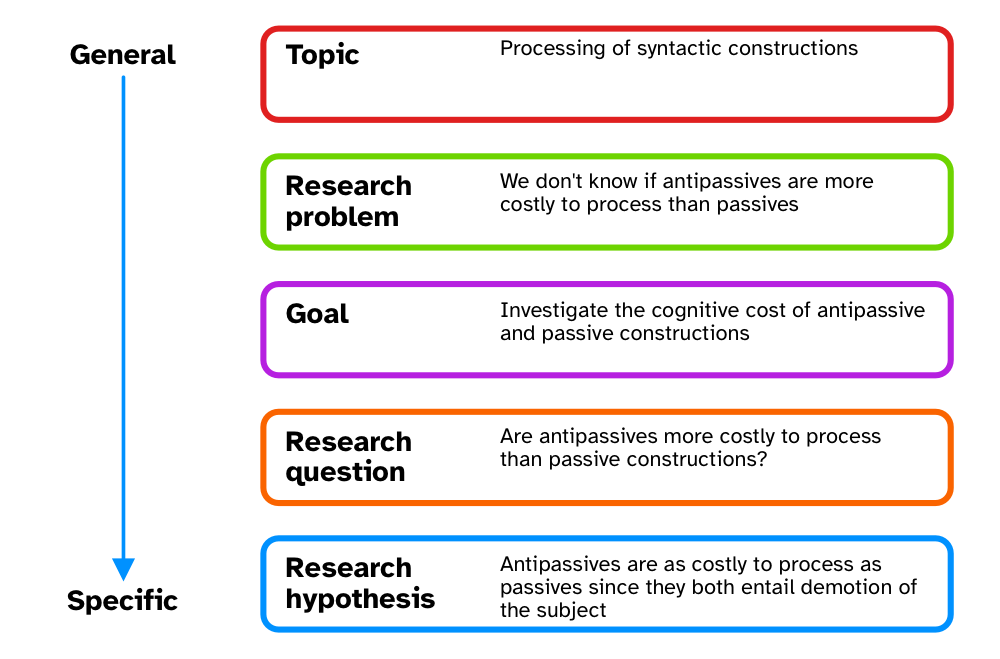

Figure 1.2 shows the main steps that compose the research process. The first component is the research context. Ellis and Levy (2008) discuss the research context and propose a convenient break-down of the concept. Figure 2.1 is a schematic representation of different aspects of the research context, from the most general to the most specific. An example of each is also provided.

The following sections treat research questions and research hypotheses in more detail.

2.1 Research questions

Research questions are questions whose answers directly address the research problem. They take the form of actual questions. For example:

- What is the average speech rate of adolescents vs that of older adults?

- What happens to infants’ syntactic processing when they move from a monolingual to a multilingual environment?

- Is the morphological complexity of languages spoken by larger populations different from that of languages spoken by smaller populations?

Research questions are always necessary, independent of the type and objective of the research. While there is an undue pressure on researcher to come up with “novel” research questions all the time, it is perfectly fine to ask the same question multiple times.

2.2 Research hypotheses

Research questions can be further developed into research hypotheses. Research hypotheses are statements (not questions) about the research problem. Hypotheses are never true nor confirmed. We can only corroborate hypothesis, and it’s a long term process. The same hypothesis has to be tested again and again, by multiple researchers in multiple contexts. Research is not a one-off matter: knowledge can only be acquired slowly and with a lot of effort. This idea has been beautifully synthesised into the “Slow Science” movement (Slow Science Academy 2010): “[Researchers] need time to think. [Researchers] need time to read, and time to fail. [Researchers] do not always know what it might be at right now.”

It is however perfectly fine to run a study with only research questions, without a research hypothesis. As long as you clearly state whether you are talking about research questions or research hypotheses and you don’t mix them up, you are fine.

2.3 Precision and testability

Solid research questions and hypotheses must have two main properties: they must be precise and testable. Precision is about the semantics of the words and phrases that make up the question or hypothesis. For example, in the question “Is the morphological complexity of languages spoken by larger populations different from that of languages spoken by smaller populations?” we need to clearly define the following: morphological complexity, larger population, smaller population. What do we mean by “morphological complexity”? How do we classify a population as large or small? For our research question to be a good research question, it is important that we think very hard about what we mean by those words. This is because depending on the specific meaning, we might obtain different outcomes, and to be sure that the outcomes answer our specific research question we need to ensure that the question itself and the words within it are well defined.

Secondly, research questions and hypotheses must be testable. Testability is about formulating research questions and hypotheses in a manner that is precise enough that it naturally leads to a well-defined, specific study design. For example, the testability of the hypothesis from Figure 2.1 would be compromised if we didn’t define “processing cost” precisely. For example, processing cost could be related to the cognitive load of processing the sentences, or to the number of “computational steps” needed to process the sentence, or to the ease of the computational steps independent of their number. All of these aspects are strictly entangled with the researcher’s assumptions and favourite linguistic framework or model of sentence processing. Very often, “fast research” leads to hypotheses that look precise and testable on the surface, but they fail to hit the mark upon greater scrutiny. Lack of precision and testability undermines the robustness of research, as pointed out for example by Yarkoni (2022), Scheel (2022), Scheel et al. (2020), and Devezer et al. (2021).

It is difficult to come by precise and testable hypotheses in linguistics just because our current knowledge and understanding of Language and languages is limited. At best, we can normally come up with vague hypotheses that state whether a difference between two conditions is expected or not and, if we are lucky, the direction of the difference (i.e. “A is greater than B” or vice versa). This state of affairs makes testing hypotheses using statistical methods less straightforward, because of the non-straightforward mapping of (vague) hypotheses to statistical models.