9 Implications and future research

This dissertation set out to investigate properties of speech production that could illuminate the debate on the origin of the effect of consonant voicing on vowel duration. While the results of this endeavour contributed to answering the questions introduced in 2.1, some open issues remain and new questions are brought to light. The following paragraphs review these and offer some final thoughts on future directions of research.

The use of nonce words in the present experiments might be seen as problematic due to the fact that they might have encouraged unnatural speech. However, using nonce words has the perk of facilitating experimental design and control over phonological factors. Note that phonetic effects like the ones under discussion can operate according to analogical processes based on stored exemplars and/or abstract representations. Hence, even if unnatural speech materials were used here, these studies should have tapped into the speakers’ knowledge, even though indirectly. Moreover, nonce words eliminate issues related to usage factors like lexical frequency, which can have a substantial influence (Hay et al. 2015; Sóskuthy & Hay 2017; Sóskuthy et al. 2018; Todd, Pierrehumbert & Hay 2019). On the other hand, neighbourhood density was not controlled for, a factor which is also known to play a role (Baese-Berk & Goldrick 2009; Goldrick, Vaughn & Murphy 2013; Seyfarth, Buz & Jaeger 2016; Glewwe 2018). It is desirable that future work investigates the patterns observed here using real words, while carefully controlling for lexical frequency and neighbourhood density, among other usage factors.

A limitation of the studies in this work is related to statistical precision of the effect estimates. As discussed throughout this dissertation, some of the effects have quite large confidence/credible intervals. In some cases, like in the cross-linguistic comparative analysis of the voicing effect, making unambiguous inferential statements becomes difficult. Possibly, much of this uncertainty derives from the sample sizes employed in these studies. Although the number of speakers included here is generally similar to or greater than average (see E), the number of observations might not have been sufficient enough to reach an appreciable degree of precision. The results discussed in this dissertation stress how important obtaining a sufficient sample is, especially when dealing with small effect sizes. Much of the phonetic literature relies on small sample sizes, but most work is done on data which is typically statistically noisy.

Moreover, arguments of effect size are very often used to make statements about what constitute a theoretically relevant effect. However, much of phonetics and phonological theory makes qualitative rather than precise quantitative predictions, and argumentations on the theoretical relevance of effect sizes at present are probably biased due to the issues discussed in 3.3. In any case, precision targets based on just noticeable differences have restricted scope. For example, Huggins (1972) shows that the perceptual threshold for segment durations varies depending on the type and baseline duration of the segment (cf. the Weber–Fechner law, Fechner 1966). Speakers can reliably detect differences of down to 5 ms with vowels that are 90 ms long (Nooteboom & Doodeman 1980). Furthermore, these perceptual thresholds might be relevant only within the task they have been elicited in, and in more natural contexts even smaller differences could be perceptible in conjunction with other, possibly more robust, cues. In sum, our current knowledge of perceptible differences is still limited, and future work should focus on investigating this matter both in light of theoretical and practical considerations. Until we can establish with certainty what differences in which contexts are physiologically impossible to be perceived, it is probably wise to report even very small, seemingly irrelevant effects while aiming at the highest level of precision possible.

This dissertation focusses on the voicing effect of stop consonants, but other manners of articulation participate in the effect. According to the compensatory account presented here, a greater difference in consonant duration should correspond to a greater voicing effect. For example, Crystal & House (1988) report a greater difference in fricative duration than in stop duration, which would be compatible with a greater voicing effect in the former. However, while House & Fairbanks (1953) and Peterson & Lehiste (1960) find that the effect is greater in fricatives than in stops, Tanner et al. (2019) observe the opposite trend. Future work should directly test the relation between differences in consonant duration and the voicing effect with consonants belonging to different manners of articulation.

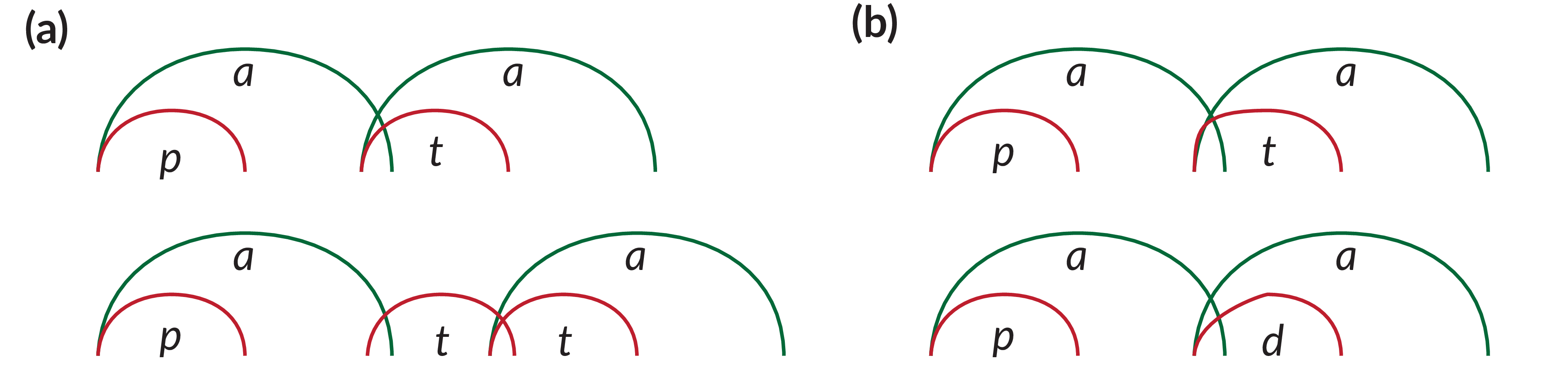

The compensatory account presented here rests on the cyclic production of vocalic gestures (Öhman 1967b; Fowler 1983). Smith (1995), Zmarich et al. (2011), and Zeroual et al. (2015)] demonstrate that the temporal distance between two vowels with an intervening stop differs depending on whether the stop is a singleton or a geminate (e.g. aba vs abba, the distance is greater in the latter case). However, I argue that the absence of vowel-to-vowel isochrony across these contexts follows from the gestural organisation of the segments involved. In the case of singleton stops, the vocalic gestures are executed consecutively and the intervocalic consonant is executed synchronously with the second vowel (Figure 9.1a top). In the case of geminates, on the other hand, the intervening consonant is the outcome of the double selection of a single gesture where the first selection is executed anti-phase with the first vowel and the second in-phase with the second vowel (Figure 9.1a bottom). The gesture of the second vowel is initiated after the completion of the intervening anti-phase gesture and in synchrony with the in-phase gesture. As a consequence, the gestural onset of the second consonant is delayed in the geminate context relative to the singleton context.

Figure 9.1: Schematics of the gestural phasing of vocalic and consonantal gestures in four different contexts. (a) shows singleton vs geminate stops, while in (b) voiceless and voiced stops are contrasted. Note that in (a) the distance between the vowels increases in the geminate context, while it is stable in (b). The different slopes of the closing part of the gesture in /t/ vs /d/ accounts for the difference in acoustic closure onset.

Future work should investigate vowel-to-vowel isochrony within contexts that have a comparable phasing profile (for example, within CV.CV words and within CVC.CV, but not across the two). The acoustic patterns discussed in this dissertation assume that the distance between the vowels in CV.CV words is not affected by the second consonant and that the timing of the gestural onset and release are the same independent of voicing, while the velocity profiles of the closing gesture differs (Figure 9.1b). By extension, I propose that the vowel-to-vowel interval should be isochronous when comparing different manners of articulation, like in pairs such as Italian /kadi/ ‘you fall’ and /kazi/ ‘cases.’ Jaw displacement could be employed as an index of the gestural timing of the vocalic gestures in plurisyllabic words (Menezes & Erickson 2013; Erickson & Kawahara 2016; Kawahara, Erickson & Suemitsu 2017). The temporal distance between the onsets or maxima of jaw displacement should be identical or very similar across voicing contexts, place of articulation, and manner of the intervening consonant.

To conclude, this work has drawn from acoustic data, ultrasound tongue imaging, and electroglottography, and a diverse set of related but contrasting languages (namely Italian, English, and Polish) with the aim of shedding new light on the widespread phenomenon known as the voicing effect. This investigation led to the development of a holistic account of the voicing effect that combines durational and articulatory aspects of previous research, complemented with diachronic considerations of the pathways that can lead to the emergence of this phenomenon. While contributing to our understanding of the voicing effect, the proposed account also opens up promising and exciting new avenues for research, which can further our knowledge in the domain of speech and language.