SQM tutorial - Week 7

Takete and maluma

We will model data from Koppensteiner et al, 2016. Shaking Takete and Flowing Maluma. Non-Sense Words Are Associated with Motion Patterns. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150610. The study looked at the relationship between sound iconicity and body motion. Read the paper abstract for an overview.

To download the file with the data right-click on the following link and download the file: takete_maluma.txt. (Note that tutorial files are also linked in the Syllabus). Remember to save the file in data/ in the course project folder.

Read and process the data

Create a new .Rmd file first, save it in code/ and name it tutorial-w07 (the extension .Rmd is added automatically!).

I leave to you creating title headings in your file as you please. Remember to to add knitr::opts_knit$set(root.dir = here::here()) in the setup chunk and to attach the tidyverse.

Go ahead and read the data. Since this file is a .txt file, you will have to use the read_tsv() function, rather than the read_csv() function. (read_tsv() is in the package readr, which comes with the tidyverse, so you don’t need to attach any extra packages for this.) Assign the data table to a variable called motion.

motion <- ...The data has the following columns:

Tak_Mal_Stim: the stimulus (MalumavsTakete).Answer: accuracy (CORRECTvsWRONG).Corr_1_Wrong_0: same asAnswerbut coded as1and0respectively.Rater: study design info.Female_0: participant’s gender (alas, as binary gender).

The study specifically analysed the accuracy of the responses (Answer) but in this tutorial we will look instead at the response itself (whether they selected takete or maluma).

Alas, this piece of information is not coded in a column in the data, but we can create a new column based on the available info.

When the stimulus is

Taketeand the answer isCORRECTthen the participant’s response wasTakete.When the stimulus is

Taketeand the answer isWRONGthen the participant’s response wasMaluma.When the stimulus is

Malumaand the answer isCORRECTthen the participant’s response wasMaluma.When the stimulus is

Malumaand the answer isWRONGthen the participant’s response wasTakete.

Now, go ahead and create a new column called Response using the mutate() and the case_when() function.

We have not encountered this function yet, so here’s a challenge for you: check out its documentation to learn how it works. You will also need to use the AND operator &: this allows you to put two statements together, like Tak_Mal_Stim == "Takete" & Answer == "CORRECT" for “if stimulus is Takete AND answer is CORRECT”.

(If you are following the documentation but case_when() is still giving you mysterious errors, make sure that your version of dplyr is the most current one. To do this, run packageVersion("dplyr") in the console. You want the output to be 1.1.0. If it’s not, you’ll need to update tidyverse by re-installing it.)

motion <- motion %>%

mutate(

...

)The column Tak_Mal_Stim has quite a long and redundant name. Let’s change it to something shorter: Stimulus.

You can do so with the rename() function from dplyr. The new name goes on the left of the equals sign =, and the current name goes on the right.

motion <- motion %>%

rename(Stimulus = Tak_Mal_Stim)If you have done things correctly, you should have a Response column that looks like this (only showing relevant columns).

motion %>%

# select() allows you to select specific columns

select(Stimulus, Answer, Response)Before moving on, here’s another challenge: Plot the response by stimulus to get a descriptive picture of what the data looks like. In other words, make a plot that tells us something about the responses given for each kind of stimulus. (To help you along, identify what kind of data this is, and think about what kind of visualisation is appropriate for this data type.)

Now we can use Response as our outcome variable!

Model Response

We want to model Response as a function of Stimulus. Since Response is binary, we have:

\[ \begin{align} \text{Resp} & \sim Bernoulli(p) \\ logit(p) & = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \cdot \text{Stim} \\ \beta_0 & \sim Gaussian(\mu_0, \sigma_0) \\ \beta_1 & \sim Gaussian(\mu_1, \sigma_1) \end{align} \]

Go through the formulae above and try to understand what is going on with each.

Now, it’s time to model the data with brm() (you need to attach the brms package):

Add the formula (referring to lecture materials if needed).

Specify the family and data.

Add

backend = "cmdstanr".Remember to save the model to a file using the

fileargument.

resp_bm <- brm(

...

)Run the model and then check the summary:

summary(resp_bm) Family: bernoulli

Links: mu = logit

Formula: Response ~ Stimulus

Data: motion (Number of observations: 460)

Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

total post-warmup draws = 4000

Population-Level Effects:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

Intercept -0.81 0.15 -1.11 -0.53 1.00 4017 2747

StimulusTakete 1.78 0.21 1.37 2.20 1.00 3743 2395

Draws were sampled using sample(hmc). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).Random MCMC

If you compare the output of your model and the output shown here, you might notice that the values for the estimates and error are different.

This is because of the random component of the MCMC algorithm: every time you re-run a Bayesian model, the results will be slightly different.

One way to make your results reproducible (i.e. they return exactly the same values every time), is to set a seed, i.e. a number that is used for (pseudo-)random generation of numbers (which is used in the MCMC algorithm).

The quickest way to set a seed is to use the seed argument of the brm() function. You can set to any number. Note that by saving the model output to a file with the file argument you are also ensuring reproducibility, as long as you don’t delete the file.

The best (and safest) practice is to both set a seed and save the output to file.

Results

Now, look at the population-level effects.

Which coefficients from the formulae above do Intercept and StimulusTakete correspond to?

Intercept

Let’s go through the Intercept together. I will leave working out the interpretation of StimulusTakete to you.

Barring small differences in the results due to the random component of the MCMC, the estimate and error for the Intercept are –0.81 and 0.15. Before moving on, test your recall: Do you remember from the lecture which unit are these estimates in?

They are in log-odds. This is because of the \(logit(p)\) part in the formula above: to model \(p\) we had to use the logit (mathematical) function, which outputs log-odds.

So now, so that we can more easily interpret and report our results, we need to convert log-odds back into probabilities. We can do that with the plogis() R function.

As an exercise, convert the estimate of the Intercept to a probability. What probability does –0.81 log-odds correspond to? Again, do this before moving on.

Since the Intercept is \(\mu_0\) from the formula above, you can say that the mean probability of \(\beta_0\) is the probability that corresponds to –0.81 log-odds (which you should have found is approximately 0.3 or 30% probability).

\(\beta_0\) is the probability of choosing “takete” when the stimulus is “maluma”. (Why? To understand this, think about the order of the levels in Response and Stimulus, and what that means for how they are coded.)

Based on the model and data, there is 30% probability of choosing the response “takete” when the stimulus is “maluma”, at 95% confidence.

StimulusTakete

Now, what about StimulusTakete? Work through this for yourself, using what you’ve learned so far.

Which coefficient in the formula above does it correspond to? How do we interpret the posterior probability of this coefficient?

How does this coefficient relate to the intercept, i.e., the log-odds of choosing “takete” when the stimulus is “maluma”?

If you’re feeling particularly adventurous, before you move on to the next section, compute the probability of choosing the response “takete” when the stimulus is “takete”.

Plotting

Let’s plot the results.

First, let’s plot the posterior probabilities of the Intercept and StimulusTakete.

Posterior probability distributions

The first step is to obtain the draws with as_draws_df().

resp_bm_draws <- as_draws_df(resp_bm)

resp_bm_drawsGo ahead, plot the density of b_Intercept (use geom_density()).

resp_bm_draws %>%

ggplot(...) +

...And separately, plot the density of b_StimulusTakete.

Conditional posterior probability distributions

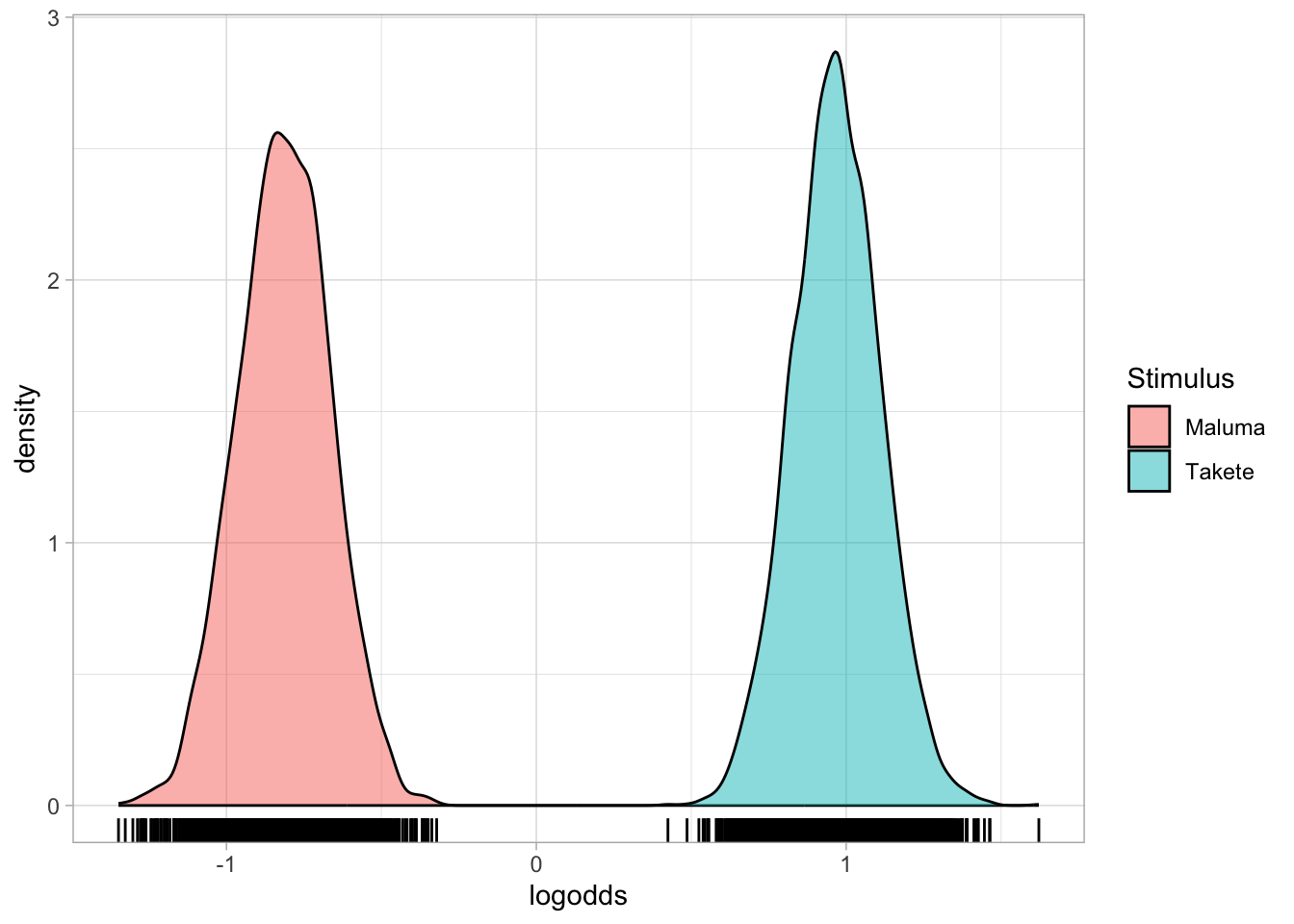

Now, let’s plot the conditional (posterior) probability distributions of the log-odds when the stimulus is “maluma” and when it is “takete”.

There are a few data-manipulation steps involved before we can get our data into a format that ggplot can handle. First up, we’ll use our draws to compute the conditional posterior probability distributions for each level of Stimulus.

Do you remember how to do this? Here’s a hint:

\(logit(p_{stim = maluma}) = \beta_0\)

\(logit(p_{stim = takete}) = \beta_0 + \beta_1\)

Identify which parts of resp_bm_draws correspond to \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\).

Now, mutate the data following the equations above, so that you have two new columns: one called Maluma and one called Takete, with the conditional log-odds of getting a “takete” response when the stimulus is “maluma” and “takete” respectively.

resp_bm_draws <- resp_bm_draws %>%

mutate(

Maluma = ...,

Takete = ...

)Now we’ve got the data we need for plotting the conditional posterior distributions, but it’s not quite in the right format yet. So let’s reformat the data so that it’s easier to plot!

At this point, you should have two columns, Maluma and Takete, each containing log-odds values. Something like this (not necessarily containing these values exactly):

Maluma Takete

-0.59 0.83

-0.53 0.93

...But plotting would be easier if we could have instead something like:

Stimulus logodds

Maluma -0.59

Maluma -0.53

Takete 0.83

Takete 0.93

...so that you could use logodds as the x-axis and Stimulus as fill.

We can achieve that by using the so-called pivot functions: they are very powerful functions, but we will only look at their simple use here.

More specifically, we need the pivot_longer() function: this is used in cases where you have columns named after some groups (e.g., our Maluma and Takete columns here), and instead you want the group names to be in a column of their own (e.g., one called Stimulus) while the values are in another column (e.g., one called logodds).

Here’s how it works (never mind the warning):

resp_bm_draws_l <- resp_bm_draws %>%

# Let's select the columns from .chain to Takete

select(.chain:Takete) %>%

# Now let's pivot the Maluma and Takete columns

pivot_longer(

cols = Maluma:Takete,

# Name of the column to store the original column names in

names_to = "Stimulus",

# Name of the column to store the original values in

values_to = "logodds"

)Warning: Dropping 'draws_df' class as required metadata was removed.resp_bm_draws_lThis looks more like what we want!

Now we can easily plot the conditional probability distributions of the response “takete” when the stimulus is “maluma” and “takete”.

resp_bm_draws_l %>%

ggplot(aes(logodds, fill = Stimulus)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.5) +

geom_rug()

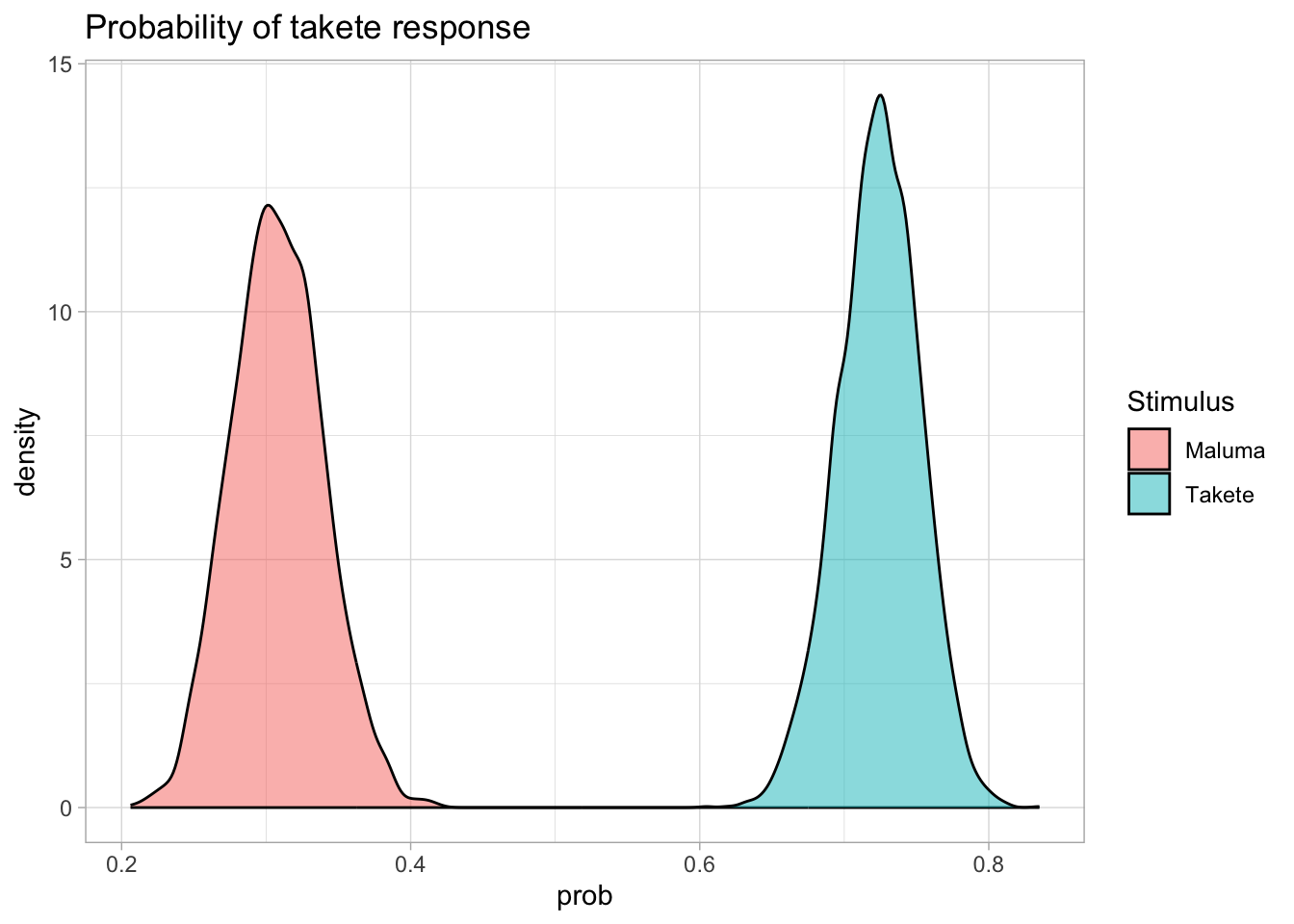

Now, this is well and good, but often it’s easier to think about our results in terms of probabilities, rather than log-odds. So what do we do if we want to plot the probability of choosing “takete”? Before looking ahead, try to guess for yourself what the solution will be.

It’s as we’ve seen before! We convert log-odds into probabilities with the plogis() function, like so:

resp_bm_draws_l %>%

mutate(

prob = plogis(logodds)

) %>%

ggplot(aes(prob, fill = Stimulus)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.5) +

labs(

title = "Probability of takete response"

)

The distributions themselves look pretty similar, but have a look at the numbers on the x axis. We’re back in probability space, hurrah!

The take-away message from this plot: We can be quite confident that different stimuli result in different probabilities of choosing “takete”, and that it is very much more probable that participants choose “takete” when the stimulus is in fact of the “takete” type!

Credible intervals

In the lecture, we learnt about the empirical rule, quantiles and credible intervals.

Now let’s look in more detail at how to obtain credible intervals (CrIs) for any probability distribution.

For sake of illustration, let’s calculate CrIs of different levels (60%, 80%, 90%) for the conditional (posterior) probabilities of the model above. (Note that you can calculate CrIs also for the (non-conditional) posterior probability distributions).

The following code uses the quantile2() function from the posterior package.

The posterior package should already be installed, but if not make sure you install it (to know if a package is installed, go to the Packages tab in the bottom-right panel of RStudio and use the search box).

Then you also need to attach the package. Add the code for attaching packages in the setup chunk and make sure you run the chunk to attach the package!

For this function, we’ll again need to use the longer-format version of the draws we obtained from our model. This data is in resp_bm_draws_l.

resp_bm_draws_l %>%

group_by(Stimulus) %>%

summarise(

# Calculate the lower and upper bounds of a 60% CrI

q60_lo = round(quantile2(logodds, probs = 0.2), 2),

q60_hi = round(quantile2(logodds, probs = 0.8), 2),

# Transform into probabilities

p_q60_lo = round(plogis(q60_lo), 2),

p_q60_hi = round(plogis(q60_hi), 2)

)We have already seen group_by() and summarise() before, so I leave understanding this part to you.

The new piece of code is quantile2(logodds, probs = 0.2) and quantile2(logodds, probs = 0.8):

- The

quantile2()function gives you the percentile based on the specified probability (theprobsargument). Soprobs = 0.2returns the 20th percentile andprobs = 0.8returns the 80th percentile. - The

round()function is used to round numbers to the nearest integer or decimal:- The second argument of

round()is the number of digits you want to round to, here2.

- The second argument of

- Finally, we convert log-odds to probabilities with the

plogis()function.

The output of the code gives us the 60% CrI of the probability of obtaining a “takete” response when the stimulus is “maluma” and “takete” respectively, both in log-odds and probabilities.

Based on the output we can say the following:

We can be 60% confident that the probability of a “takete” response is between 28% and 33% (–0.94 to –0.69 in log-odds) with the “maluma” stimuli, and it is between 70% and 75% with the “takete” stimuli.

Nice!

Now I leave to you calculating the 80% and 90% CrIs. Can you tell which values to use with the probs argument for an 80% and 90% interval?