Mindless statistics and the ‘null ritual’

University of Edinburgh

2025-05-01

Quiz

Suppose you have a treatment that you suspect may alter performance on a certain task. You compare the means of your control and experimental groups (say 20 subjects in each sample). Further, suppose you use a simple independent means t-test and your result is significant (t = 2.7, d.f. = 18, p = 0.01).

You have absolutely disproved the null hypothesis (that is, there is no difference between the population means).

You have found the probability of the null hypothesis being true.

You have absolutely proved your experimental hypothesis (that there is a difference between the population means).

You can deduce the probability of the experimental hypothesis being true.

You know, if you decide to reject the null hypothesis, the probability that you are making the wrong decision.

You have a reliable experimental finding in the sense that if, hypothetically, the experiment were repeated a great number of times, you would obtain a significant result on 99% of occasions.

True or false?

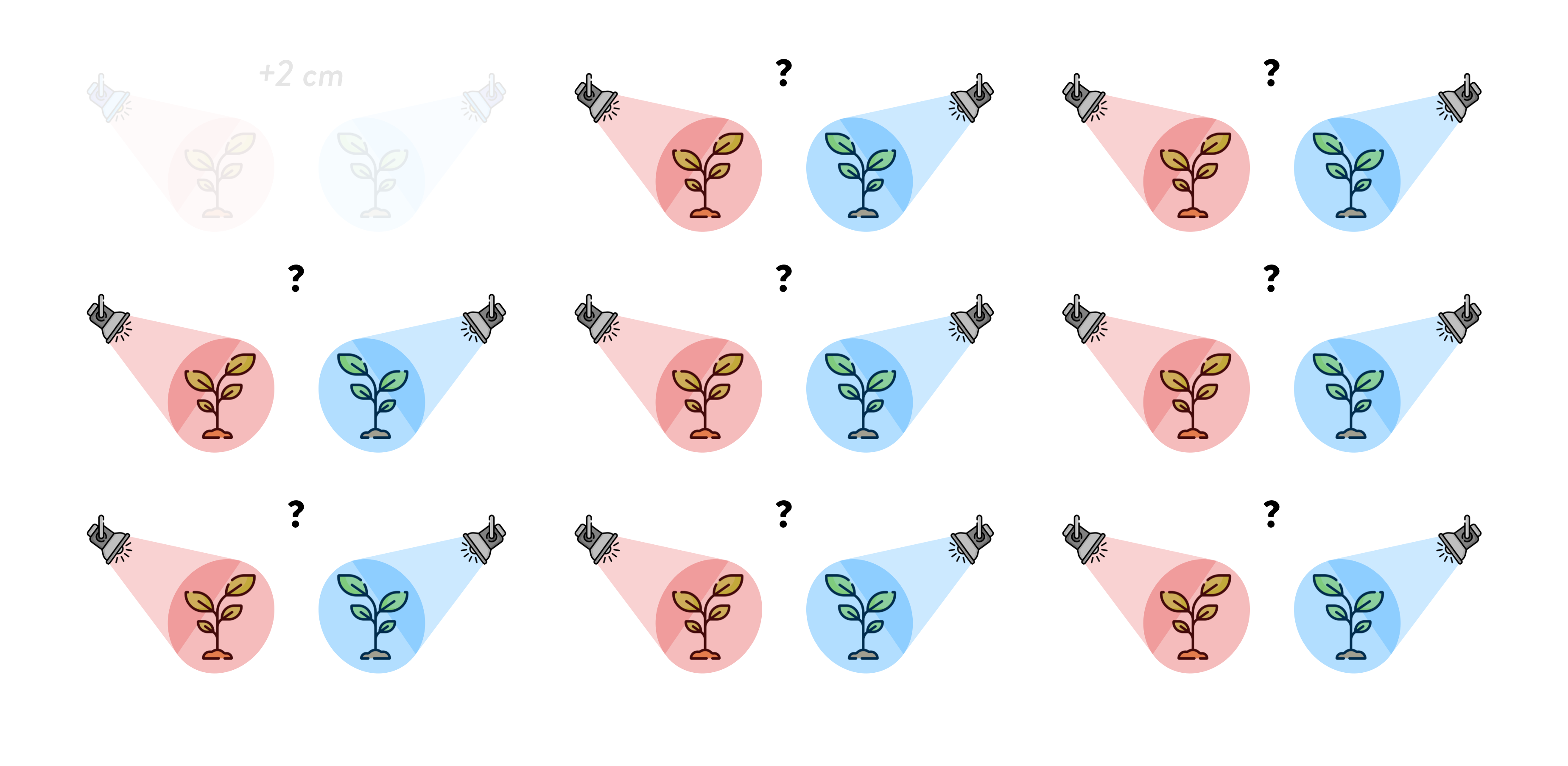

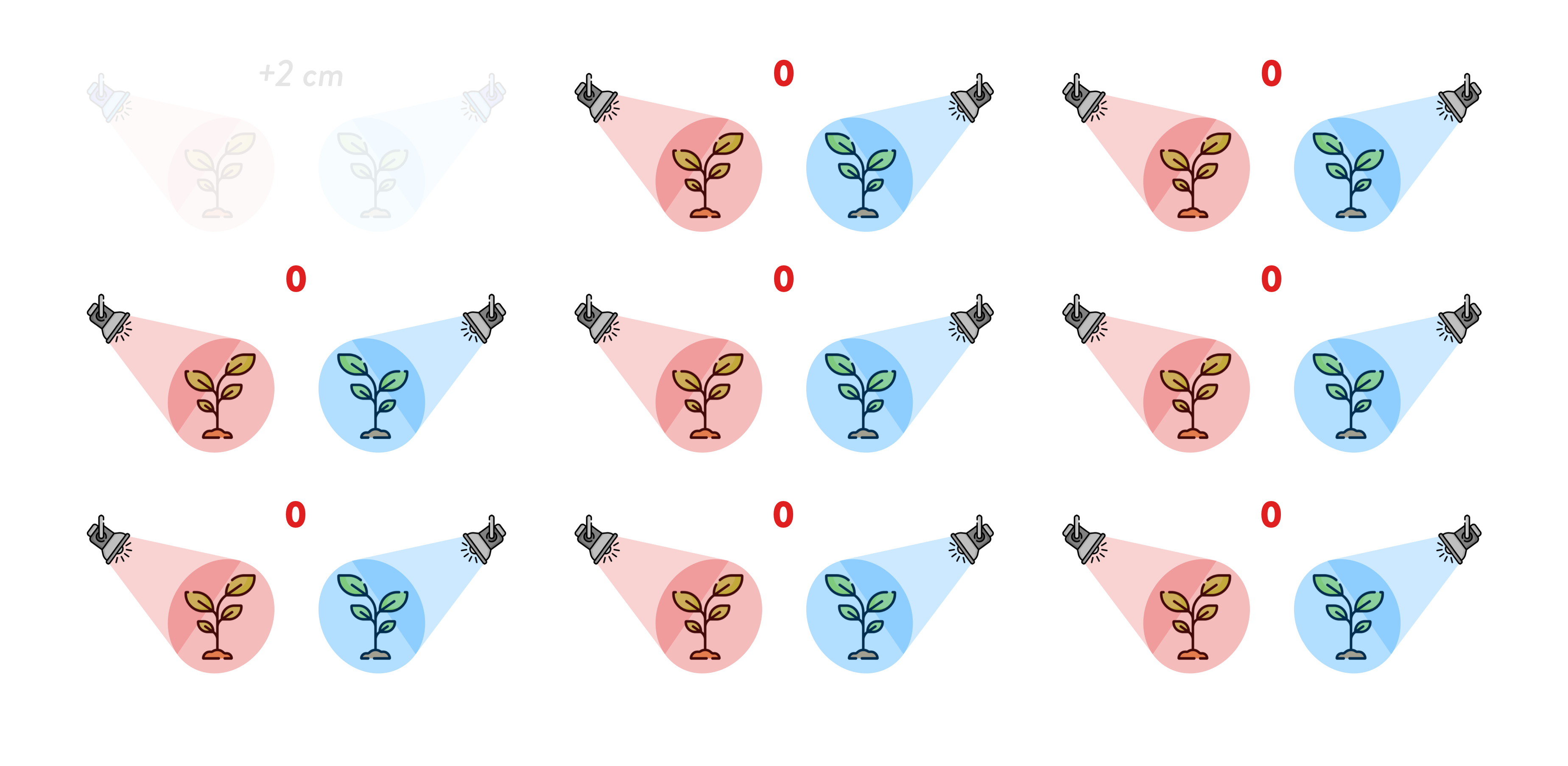

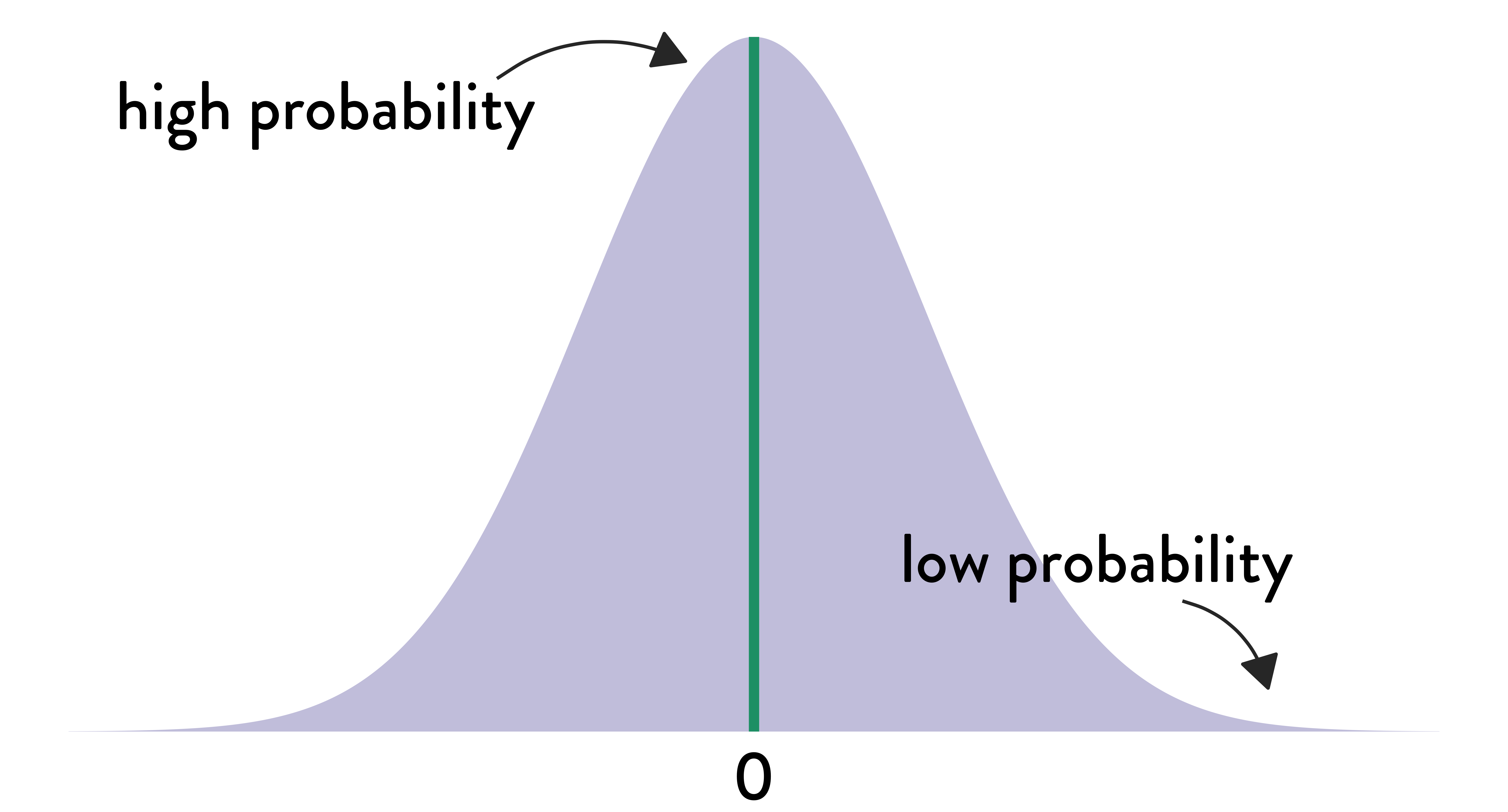

Growing plants on Mars

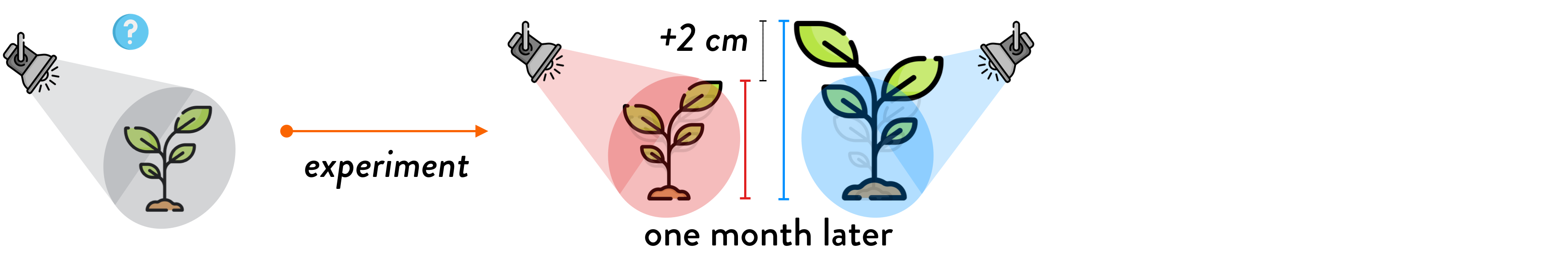

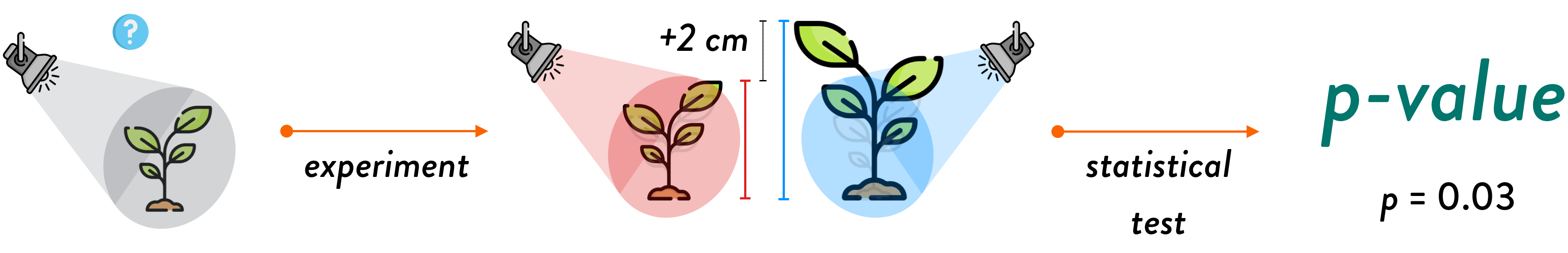

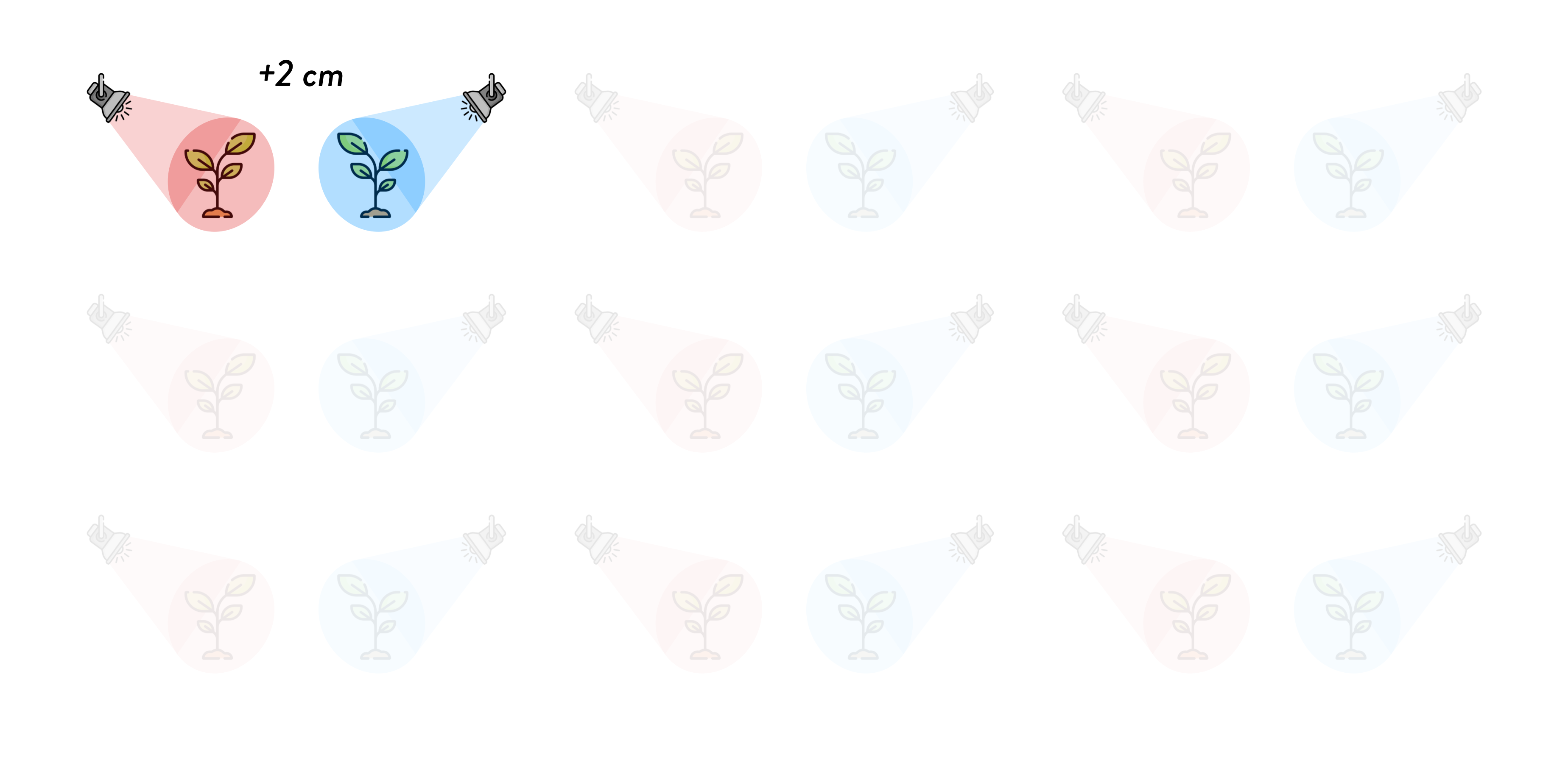

Will different light colour affect growth?

Will different light colour affect growth?

Will different light colour affect growth?

Will different light colour affect growth?

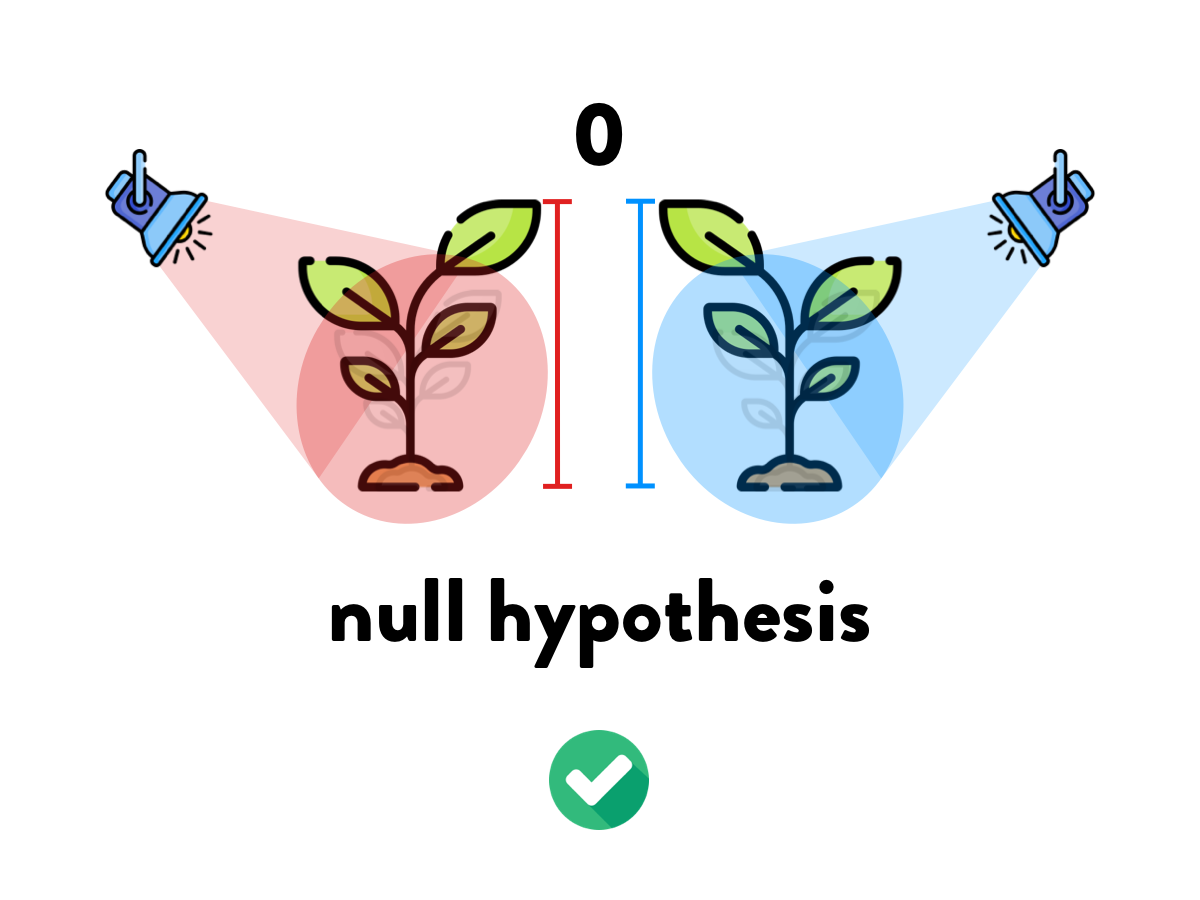

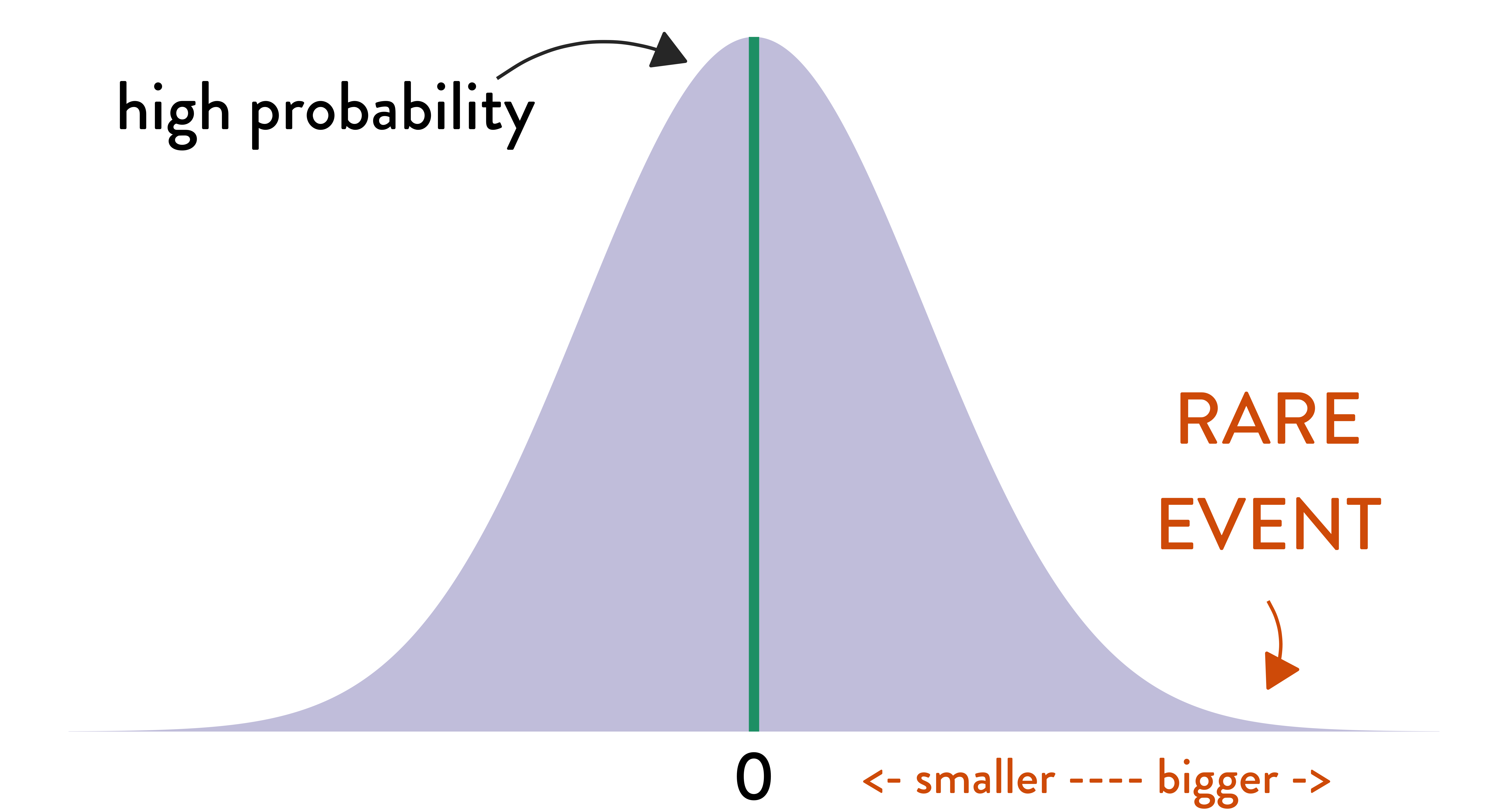

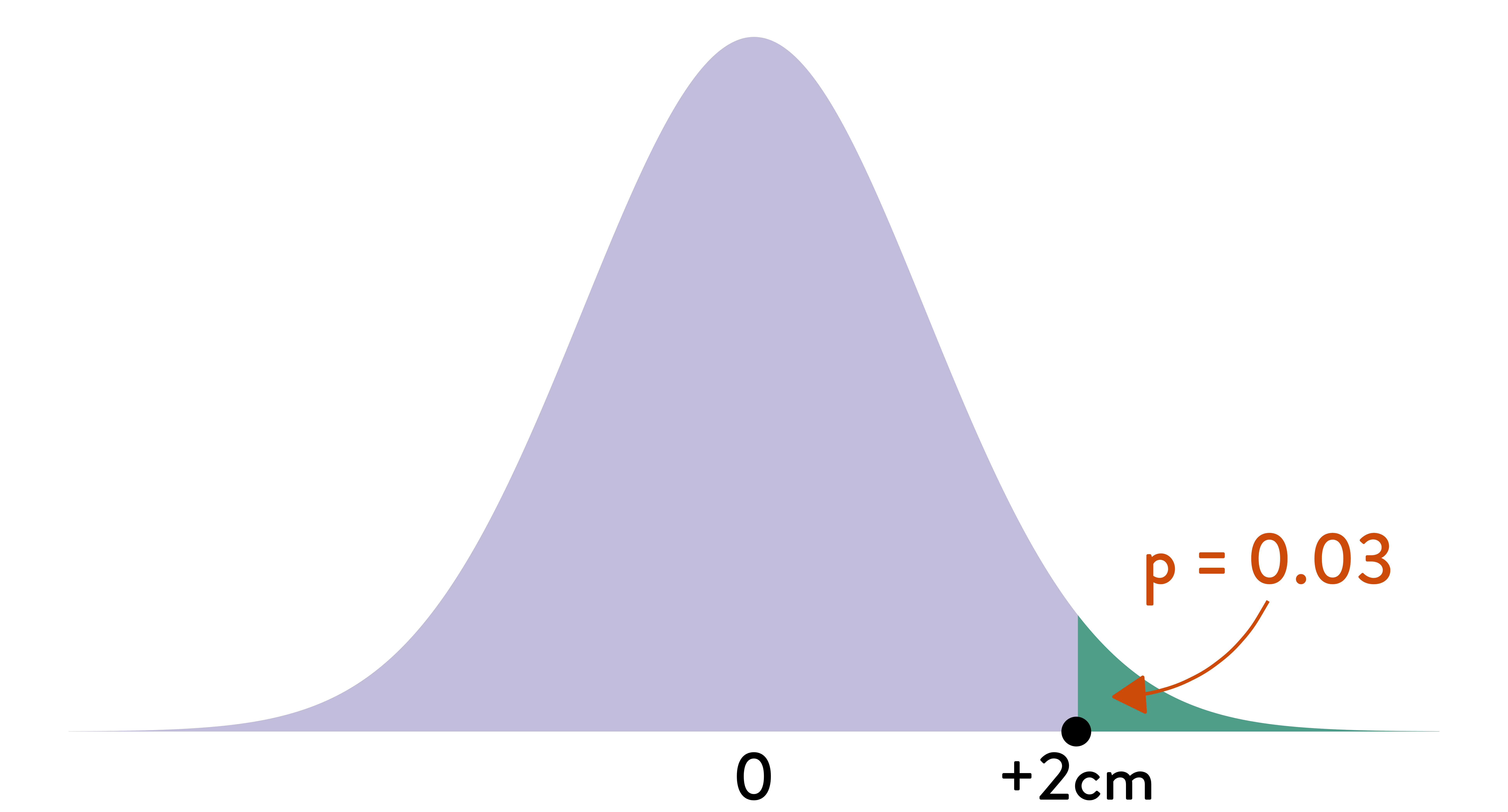

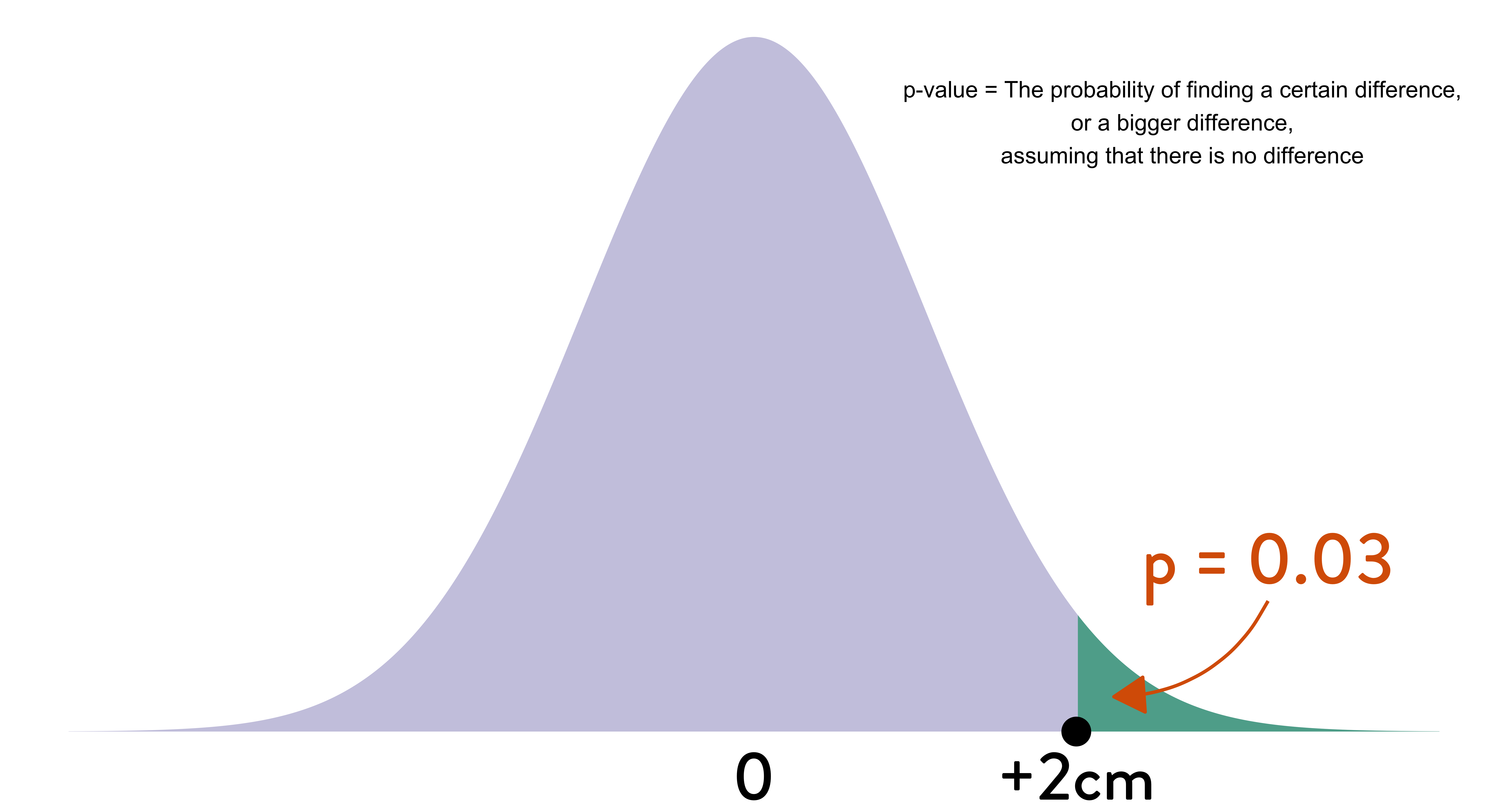

The \(p\)-value

The \(p\)-value

The \(p\)-value

The \(p\)-value

The ‘null ritual’

Gigerenzer (2004), Gigerenzer, Krauss & Vitouch (2004), Gigerenzer (2018).

Set up a statistical null hypothesis of “no mean difference” or “zero correlation.” Don’t specify the predictions of your research hypothesis or of any alternative substantive hypotheses.

Use 5% as a convention for rejecting the null. If significant, accept your research hypothesis. Report the result as p < 0.05, p < 0.01, or p < 0.001 (whichever comes next to the obtained p-value).

Always perform this procedure.

Why is it problematic?

The null ritual would have been rejected by the statisticians it is attributed to.

- Fisher rejected each of the steps above towards the end of his life.

- “Null” does not mean “nil” but “to be nullified”.

- Fisher thought that using a routine 5% level of significance indicated lack of statistical thinking.

- Null hypothesis testing was the most primitive of analyses (only when no or very little knowledge.

- Neyman and Pearson rejected null hypothesis testing and favoured competitive testing between two or more hypotheses.

Fisher’s null hypothesis testing

Set up a statistical null hypothesis. The null need not be a nil hypothesis (i.e., zero difference).

Report the exact level of significance (e.g., p = 0.051 or p = 0.049). Do not use a conventional 5% level, and do not talk about accepting or rejecting hypotheses.

Use this procedure only if you know very little about the problem at hand.

Neyman–Pearson decision theory

- Set up two statistical hypotheses, H1 and H2, and decide about \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), and sample size before the experiment, based on subjective cost-benefit considerations. These define a rejection region for each hypothesis.

- If the data falls into the rejection region of H1, accept H2; otherwise accept H1. Note that accepting a hypothesis does not mean that you believe in it, but only that you act as if it were true.

- The usefulness of the procedure is limited among others to situations where you have a disjunction of hypotheses (e.g., either \(\mu_1 = 8\) or \(\mu_2 = 10\) is true) and where you can make meaningful cost-benefit trade-offs for choosing alpha and beta.

Level of significance

- Early Fisher

- Mere convention of 5%.

- Neyman and Pearson

- \(\alpha\): probability of wrongly rejecting \(H_1\) (vs \(H_2\)), Type-I error

- Later Fisher

- Rejects idea of convention and Type-I and II errors.

- Exact level of significance, i.e. exact \(p\).

- “You communicate information; you do not make yes–no decisions.” (Gigerenzer 2004: 593).